The legal sphere may not be a physician’s natural habitat, but it is an area in which a medical professional’s knowledge and experience can be instrumental. According to a recent report, the call for evidence-based and experience-based medical opinions in legal cases has been on the rise (StatPearls [Internet]. https://tinyurl.com/2ndm5j99). Understanding this, many professional medical societies, including the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS), provide their members with specific recommendations or guidelines for serving as expert witnesses (AAO-HNS. https://tinyurl.com/mszk2t23).

The legal sphere may not be a physician’s natural habitat, but it is an area in which a medical professional’s knowledge and experience can be instrumental. According to a recent report, the call for evidence-based and experience-based medical opinions in legal cases has been on the rise (StatPearls [Internet]. https://tinyurl.com/2ndm5j99). Understanding this, many professional medical societies, including the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS), provide their members with specific recommendations or guidelines for serving as expert witnesses (AAO-HNS. https://tinyurl.com/mszk2t23).

For physicians who embrace the call, providing expert medical testimony is both enriching and enlightening. For many others, however, it is a foreign territory. “The medical–legal world is a big black box for most physicians. We get no training in it and don’t know much about it,” said David Terris, MD, regents professor of otolaryngology– head and neck surgery and surgical director of the Augusta University Thyroid and Parathyroid Center in Georgia. Dr. Terris has been doing expert witness work since 1994, with a focus on the thyroid and parathyroid specialties. “For me, [this work] has offered two great opportunities: one, to help some of my colleagues in need of good expert witness testimony, and two, to exercise a different part of my brain.”

Requirements and Expectations

Providing medical expert testimony involves several phases: engaging in thorough preparation to form an opinion, participating in an interrogatory (written discovery), sitting for a deposition (oral discovery), and, in some cases, testifying before a trial jury. The preparation period involves reviewing all the materials and records relevant to the case, including others’ depositions. Through this process, the physician forms their opinion. “It’s like cramming for a final exam,” Dr. Terris said. “You want to be totally prepared for the questions that you’re going to get in your deposition, to have the important facts of the case at your fingertips. That’s a commitment that one needs to make at the outset.”

“In general, your opinion is going to be based on your fund of knowledge, and not on outside references,” said M. Boyd Gillespie, MD, MSc, professor and chair of the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis. “However, occasionally there is a situation in which one side is making the case seem less complex than it is, and you may need to pull some literature that would be helpful and offer it to the side that you’re working with as potential evidence for the case.”

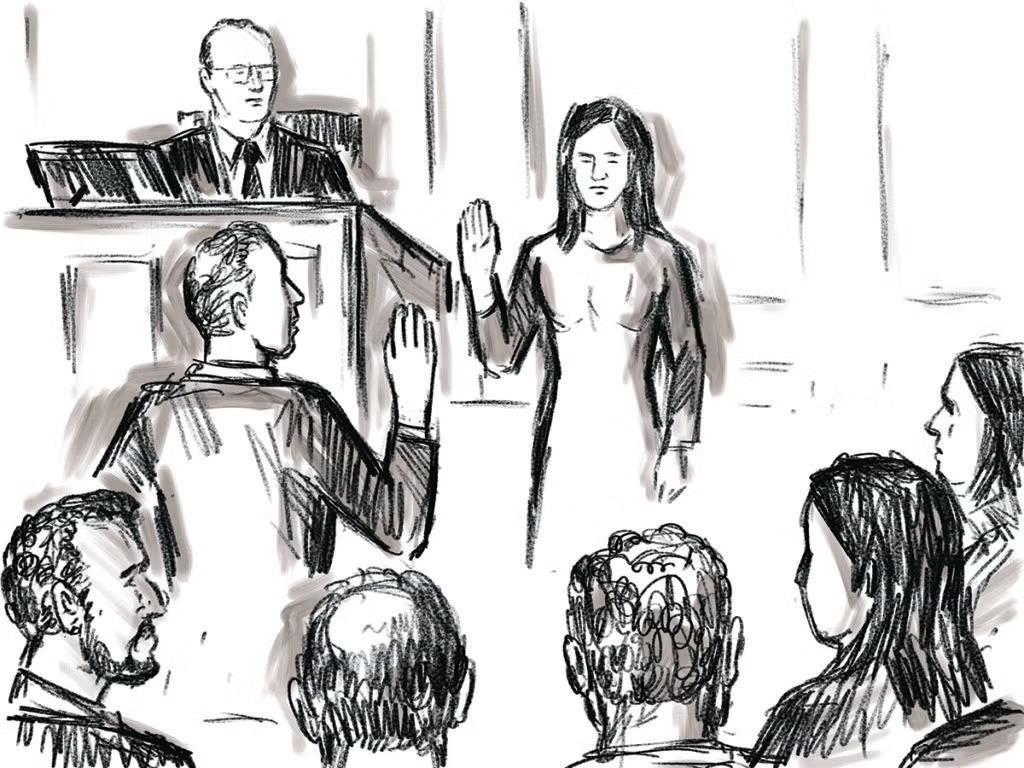

For the interrogatory, the physician witness is asked to respond to written questions that will likely include those about their own background and training. The deposition, which might come months or even years after the case has begun, is conducted under oath and recorded. As for the trial, most medical cases never get that far; it is usually in everyone’s best interests to settle out of court. If a trial does occur, the physician witness will be asked to respond to questions posed by both the defense and the plaintiff’s attorney from the witness stand.

It is important to note that a physician’s notes on the case, as well as any communications between the physician and the attorney, are considered legally admissible in court—a fact that Dr. Terris learned the hard way. “Preparing for my first deposition, I did not know that attorney–client privilege does not apply to expert witnesses, meaning that all my notes and correspondence with the attorney—emails and texts—were discoverable,” he recalled. “So, during the deposition, the attorney asked if I’d made any notes, and I said yes and handed them over. There were some things I might not have included in there. Also, whereas normally a deposition lasts anywhere from 90 minutes to three hours, in my very first deposition, I was tortured for nine hours!”

Julie Wei, MD, is the Dr. Alfred J. Magoline, MD Endowed Chair in the division of pediatric otolaryngology at Akron Children’s Hospital and professor of otolaryngology head-neck surgery at Northeast Ohio College of Medicine and University of Central Florida College of Medicine. Dr. Wei stresses the importance of using the preparation period to become familiar with the medical records and other specifics pertaining to the case. “I make sure I have a clear understanding of the timeline of events, as well as what is stated in the affidavit of the other side’s expert witness, and the depositions of the defendants or those involved and named in the suit,” she said.

Before opening a single file, however, the physician must honestly evaluate whether they are the right person for that case. “I’m board certified in otolaryngology, and I can practice the whole gamut of otolaryngology and pediatric ENT as well, but I primarily do legal cases within my sub-specialty of voice and swallowing, breathing disorders—basically the pharynx, larynx, and trachea,” explained Gregory Postma, MD, professor of otolaryngology and director of the Medical College of Georgia Center for Voice, Airway, and Swallowing Disorders in Augusta, who became involved in legal work 25 years ago. “That said, there is considerable overlap between this and other ENT sub-specialties.”

Before opening a single file, however, the physician must honestly evaluate whether they are the right person for that case. “I’m board certified in otolaryngology, and I can practice the whole gamut of otolaryngology and pediatric ENT as well, but I primarily do legal cases within my sub-specialty of voice and swallowing, breathing disorders—basically the pharynx, larynx, and trachea,” explained Gregory Postma, MD, professor of otolaryngology and director of the Medical College of Georgia Center for Voice, Airway, and Swallowing Disorders in Augusta, who became involved in legal work 25 years ago. “That said, there is considerable overlap between this and other ENT sub-specialties.”

Should a physician witness ever work for the plaintiff’s side? Absolutely, say experts. It speaks to the integrity and credibility of the witness. “I encourage everybody to do work on both sides,” Dr. Postma said. “I prefer defense—I think that’s almost everyone’s bias—but we’re not only trying to defend doctors that may have had a bad outcome when they’ve not done anything beyond the standard of care. It’s also important that we police our profession. That’s part of taking care of patients around the country. Now, there are doctors who, by reputation, only do plaintiff cases, which basically says you’re simply a hired gun; someone gives you a retainer and you say whatever they want you to say. That’s the kiss of death for someone in academic medicine.”

The prospective expert witness should also make sure they are prepared to commit considerable time and energy to the case. “I was initially surprised at how much time it takes to do this type of work,” Dr. Wei said. “The process takes a long time, and it can even be emotionally exhausting, particularly when it concerns a bad outcome for a pediatric patient. As a parent, I have to manage my reactions to focus entirely on the facts.”

Getting Started

How does a physician find their way into doing legal case work? Some, like Dr. Terris, had someone to guide them. “I was fortunate to have a mentor, Bill Fee, who was the chair of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Stanford University, where I trained and worked,” he said. “He referred some cases to me and kind of showed me the ropes and walked me through the process. That was extraordinarily helpful.”

Dr. Gillespie became interested early in his academic career. “Some of the more senior physicians in my practice were doing this sort of work,” he said. “They thought it was a good side gig that was also a way to serve the profession. Also, my wife is an attorney, so I had some exposure to law and always found her work and career interesting.” Referrals to Dr. Gillespie as an expert witness have been via word of mouth. “I’ve never gone out seeking expert work or had services advertised, which is frowned upon anyway. I was practicing in South Carolina. If I remember correctly, I started getting referrals from our major malpractice carrier to review cases involving colleagues within the state.”

Once relationships are formed, the offers tend to come. “You do one case, then word gets out, and your name gets suggested,” Dr. Postma said. “I’ve done lots of cases for the same groups of attorneys. If things go well and you have a good relationship with a given team, then you’re likely to be contacted for something again in the future.” He enjoys the challenge and likens it to detective work. “It may sound odd, but it’s kind of fun in that you get to go through the facts and figure out exactly what happened and what was the thought process of given individuals,” he said. “Sometimes there are interesting surprises when you do that. I’ve found things that were previously missed.”

Dr. Wei was drawn into expert witness work partly out of “curiosity and a desire to learn about the legal system, as we physicians have no training in this whatsoever,” and partly due to her own experiences of being named in lawsuits, once as an intern and twice as an attending. “Regardless of ‘fault,’ if a patient is injured, or even if a lawsuit and claim are unfounded, we physicians and surgeons are not prepared to endure such an emotionally and potentially professionally devastating experience, which is so prevalent in the U.S.,” she said. “I also wanted to learn what I can do better as a surgeon, what exactly constitutes medical negligence, and what system-based issues and personal practice patterns put patients in harm’s way.”

A pediatric otolaryngologist, Dr. Wei served on her first legal case in 2010. “A law firm reached out, and I was retained as an expert witness for the plaintiff side,” she said. “A healthy child had undergone T&A [tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy] at a surgery center, then went home and bled to death. Despite my over-busy schedule, I spent many nights and weekends reviewing every detail of the case. As the highest volume surgeon at a university outpatient surgery center, I was motivated to understand these details and compare them with my own experience and observations. Providing my assessment and expert opinion about what was considered standard of care, our practice guidelines, involvement with national societies, and working with colleagues across the country, I garnered a wealth of information—while I grieved the reality that we simply don’t talk enough about risks and complications in ‘routine’ cases.”

Navigating the Legal World

For medical professionals, operating within the legal sphere involves a learning curve and a period of adjustment. Legal terminology is a good example. “I’ve seen so many cases where people are asked, ‘What is the definition of “standard of care”?’ and they struggle,” Dr. Terris said. “Even though we as physicians don’t think about the legal definition of the term, you need to understand it if you’re going to do this kind of work.”

The pace of legal proceedings is infamously slow, a fact that has astonished physicians who work on medical cases. “I think if you asked in a questionnaire to physicians what surprised them most about being expert witnesses, the absolute number one answer would be the length of time the process takes,” Dr. Postma said. “It can be so unbearably drawn out, it’s downright funny. Like, one weekend I’ll be looking at a box of legal material in my study, and there’s dust on it because it has been two years. So, I call the attorney on the case, and she says, ‘Oh, it’s still moving.’”

Dr. Gillespie recalls a case he worked on for which a trial date had been set, but which was ultimately dropped by the plaintiffs. “They realized they were going to lose,” he recalled. “But it had gone on for six years! I told one of the attorneys, ‘You know, they built Hoover Dam in four years.’ It can be excruciating for the defendant physician, who may feel scrutinized and impugned as this process plays out.” Indeed, lawsuits can take a high emotional toll on the medical professional defendant. “It can be lonely for them, so serving as an expert on the defense side, you feel like kind of a friend to that practitioner,” Dr. Gillespie said.

One of the steeper areas of the learning curve concerns the ability to answer attorneys’ questions accurately and concisely. “If you’re going to do this kind of work, it’s your obligation to anticipate what questions you’re going to be asked and make sure you’re ready to answer them,” Dr. Terris said. “I feel a certain amount of pressure to perform well. Good attorneys can help with that process, especially in preparing a less experienced witness.”

Listening skills become especially important. “You can’t be thinking of your answer before the question is asked,” Dr. Gillespie said. “You have to listen to the wording of the question. My most acute listening skills are probably applied during depositions and testimonies.” A common mistake witnesses make is talking too much during the deposition. “Just listen to the question and then answer it. If it’s a yes/no question, your answer should be either yes or no,” Dr. Terris cautioned. “It shouldn’t expound beyond that, except in rare circumstances.” Expounding becomes necessary, says Dr. Gillespie, “when the question is asked in a way that will make a yes or no answer sound like you’re saying something against the side you’re representing. You have a right to expound upon your reasons for answering a certain way, as in ‘Yes, but in this circumstance’… etc. Take the time to make these points during the deposition because it is meant to get your opinions on the record.”

Maintaining such self-discipline during questioning can be challenging, especially during a trial, when the proceedings can become rather performative. “I think the important thing is not to become impatient with the questions you’re being asked, particularly when they’re repetitive and perhaps designed to get a rise out of you,” Dr. Postma said. “I tell my former fellows who are doing this, the attorney will do everything they can, especially during the trial, to make you look like a money-hungry doctor. ‘Dr. Jones, how much do you charge for your witness services?’ the attorney will ask, then turn to the jury with an expression of astonishment. And the jury looks at you: ‘Wow, that’s how much you charge?’ When a case goes to trial, it becomes a show.”

The best way to counter these maneuvers, experts say, is not to take the bait. “You don’t want to be antagonistic,” Dr. Postma said. “I’ve read depositions and seen trials where people are just dripping with arrogance and condescension. It doesn’t help your argument. You want to look like a real person as well as an expert, especially on the defense side. What’s that cliché? ‘There but for the grace of God, go I.’ We all have issues and complications in our practices. Show humility.”

Serving as a medical expert witness can be challenging and time-consuming, but for those who participate, it is a rewarding and satisfying experience. “I think our legal system works better when there are knowledgeable people in good standing making sure that these issues are properly resolved,” Dr. Gillespie said. “So, I would certainly encourage my colleagues to engage in this process.”

Linda Kossoff is a medical journalist based in Los Angeles.

Leave a Reply