INTRODUCTION

Endolymphatic sac surgery has long been the subject of debate, both in terms of its success rate and the technique to be adopted. Recently, Saliba et al. demonstrated a higher success rate for endolymphatic duct blockage than for the decompression and shunt techniques. It has been found to provide very satisfactory control of vertigo, and also seems to be beneficial to hearing, although this aspect has yet to be developed.

However, the successful implementation of this technique relies heavily on precise identification of the endolymphatic sac or duct to position the clips correctly and achieve blockage. Locke et al. emphasized the great variability in the anatomy of the endolymphatic sac and the difficulties encountered when it is approached via the transmastoid route.

In this study, we share our experience in managing the anatomical variations of the endolymphatic duct.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study examines the surgical approaches and anatomical variations of the endolymphatic sac encountered during transmastoid procedures. These variations are influenced by the duct’s width, trajectory within the petrous bone, and overall accessibility. We provide detailed descriptions of surgical techniques tailored to each anatomical scenario, supplemented with illustrative surgical footage.

RESULTS

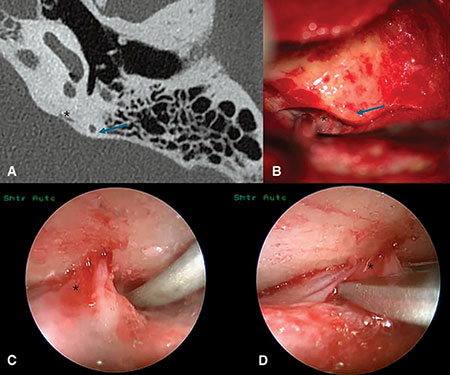

Figure 1: “Narrow” anatomical type: pre-operative axial CT scan view (A), perioperative microscopic view (B), 30° endoscope visualization (C), and clip positioning (D). * endolymphatic duct; blue arrow: posterior semi-circular canal.

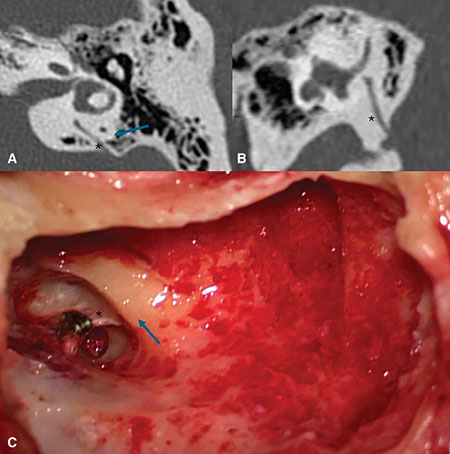

Figure 2: “Broad” anatomical type: pre-operative axial (A), and coronal (B) CT-scans, perioperative view (C) * endolymphatic duct; blue arrow: posterior semi-circular canal.

Temporal bone imaging and intra-operative findings of two caricatural presentations are shown in Figure 1 (“narrow” anatomy) and Figure 2 (“broad” anatomy). In the first situation, the endolymphatic sac is mostly located within the dura of the posterior fossa, and only a narrow duct is situated in the petrous bone. In broad anatomical types, there can be a large trapezoidal duct in the petrous bone, contained within an elliptical-shaped bony canal and often surrounded by mastoid cells or bone, depending on the pneumatization. These differences may lead to the use of different surgical approaches.

In all cases, a usual transmastoid approach is used, with retroauricular incision and drilling until visualization of the incus short process, tegmen mastoideum, and lateral semi-circular canal is achieved. The course of the mastoid segment of the facial nerve can be identified below the bony labyrinth, enabling safe drilling of the sub-facial mastoid cells. This exposure will be particularly useful if the duct is broad, to avoid neglecting the antero-inferior edge of the endolymphatic sac during blockage. Depending on the patient’s anatomy, particularly in narrower anatomical types, it can be useful to drill around a bony island on the sigmoid sinus to medialize it and increase the exposure of the posterior fossa dura.

Once all these landmarks have been established, the technique will differ according to the patient’s anatomy. If the anatomy is narrow and/or the operculum is located medial to the posterior semicircular canal, it is almost systematically necessary to recline the posterior fossa dura to satisfactorily expose the endolymphatic duct (Fig. 1). This involves removing the bone from the posterior fossa dura between the sinus and the posterior semi-circular canal, using smaller and smaller diameter diamond burs to avoid injury to the posterior semi-circular canal and posterior fossa dura. Elevating the dura from the bone above and below the supposed level of the endolymphatic sac will help the surgeon to visualize it. The duct, entering the operculum, can be identified as a duplication of the dura, stretched between the posterior fossa dura and labyrinth. Donaldson’s line (parallel to the lateral semi-circular canal and bisecting the posterior canal) is a useful landmark for approximating the location of the operculum. To limit confusion with vessels or adhesions, which can exist superficially, CT scan measurements may be obtained between the posterior canal and the assumed duct location and checked intra-operatively. Once the duct is identified, positioning the clips becomes relatively straightforward because the dura can be lowered with the clip pliers, which can then surround the duct. In difficult cases, visualization of the duct and clip positioning can be aided by endoscopy if exposure remains unsatisfactory after extensive drilling and detachment of the dura (Fig. 1). The risk of a cerebrospinal fluid leak is higher in “narrow” anatomical situations, as these require extensive manipulation of the dura. Based on the authors’ experience, this complication is most likely to occur during the drilling and exposure of the posterior fossa dura. In such cases, the approach will depend on the size of the tear. Management involves the use of various connective tissue grafts—such as superficial temporal fascia, muscle, or fat—potentially combined with biological adhesives.

The complication may also occur when exposing a deeply situated operculum during dissection of the endolymphatic sac, either prior to or during insertion of the clips. This situation is relatively frequent, but the meningeal tear is generally limited and will be spontaneously sealed by the posterior wall of the temporal bone once manipulation of the posterior fossa dura is completed. Employing connective tissue grafts to reinforce the injured area can provide an additional layer of safety.

If the duct within the mastoid is large, and especially if the operculum is superficial relative to the posterior canal, duct identification is generally more straightforward. The challenge in such cases lies in clipping the entire width of the duct—which can be substantial—and ensuring the clips are appropriately tightened.

The authors recommend exposing the cells adjacent to the posterior semicircular canal to access the most distal—and therefore narrowest—portion of the duct. Additionally, exposing the sub-facial cells is advised to properly identify the antero-inferior edge of the duct. To ensure proper tightening of the clips, it may also be necessary to drill the cells medial to or beneath the endolymphatic duct, creating space for the clip pliers. This approach, as shown in Figure 2, facilitates the process.

At this stage, it becomes possible to slide the uncoupled clips across the full width of the duct and tighten them in a subsequent movement, using the created space to position the clamp effectively.

Leave a Reply