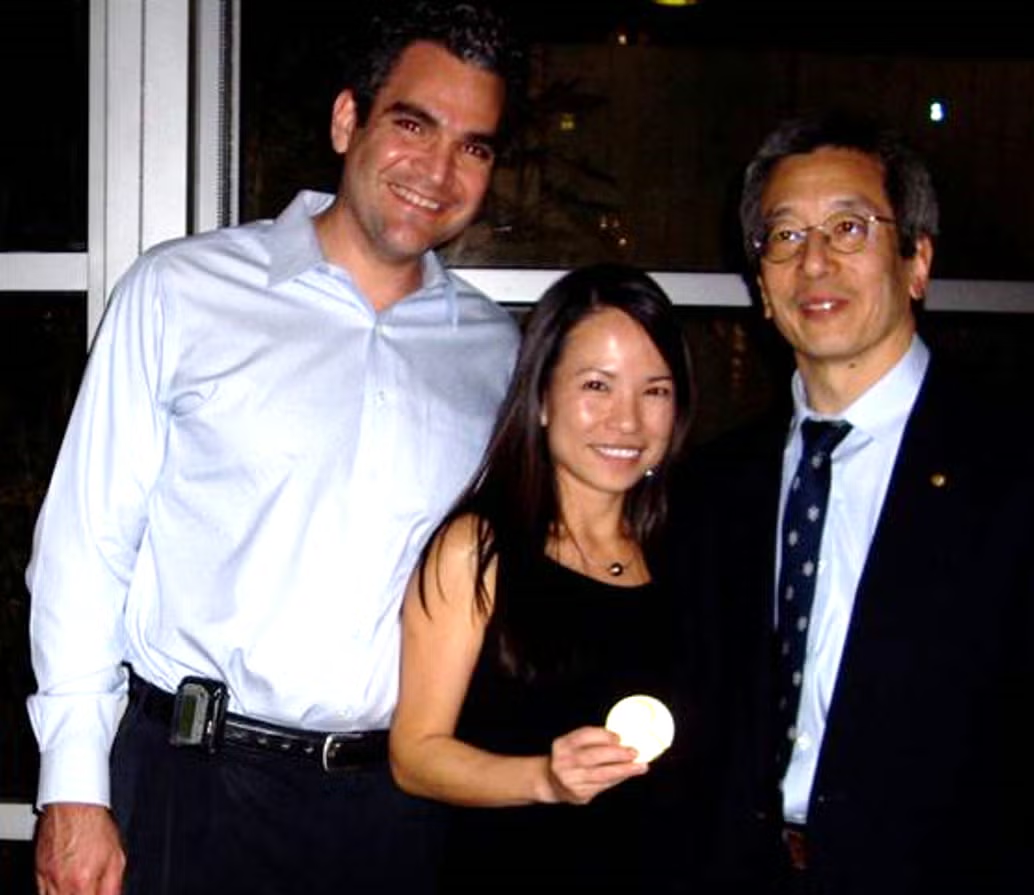

Dr. Nguyen holding Dr. Roger Tsien’s (right) Nobel Prize medal in 2008, at the celebratory dinner with her husband, Brett Berman (left)

If you spend even five minutes with Quyen Nguyen, MD, PhD, you immediately understand why colleagues describe her work as visionary and her presence as grounding. She speaks with a blend of wonder, precision, and generosity that makes you feel as if you’re discovering the field anew, right alongside her.

Dr. Nguyen, professor and neurotologist at UC San Diego, has spent more than two decades pursuing an idea that first grew quietly in the back of her mind as an ENT resident: What if surgeons could simply see nerves? Not through guess-work, experience, or anatomical memory—but truly see them, glowing against surrounding tissue? That question now sits at the center of her “in-human” clinical trial evaluating Bevonescein, a fluorescent nerve-labeling molecule she co-invented with the late Nobel laureate Dr. Roger Tsien.

Our conversation began, not with molecules or microscopes, but with our shared love for people and the stories that form the fabric of our specialty.

This interview was condensed and edited for clarity.

Dr. Rapoport: You shared a beautiful story with me about attending the “Forbes 50 Over 50” event, where a 78-year-old honoree said she sees time as a canvas, not as a linear road. How did her comment resonate with you?

Dr. Nguyen: That moment has stayed with me. She said a woman doesn’t have to move through time in a straight line— we can reinvent ourselves whenever we want. As a mother of three daughters and a working physician–scientist, I felt that deeply. You want your children to know they can do anything, at any time, and that their life isn’t limited by a prescribed timeline. I try to center that lesson at home and in my career.

Dr. Rapoport: What initially drew you to medicine and, more specifically, to the field of otolaryngology?

Dr. Nguyen: I recently attended our Academy’s meeting in Indianapolis, where I heard Dr. Jim Netterville’s keynote address. He said the meaning of life for him is to be in service to others. As physicians, we give cures, and we give hope. And when we can’t provide either, we give comfort. Decades after my initial decision to pursue medicine, I believe that he articulated the most succinct way to describe why this profession is important to me. I can’t imagine anything more meaningful than to be helpful when someone is in their greatest moment of need.

As for ENT—I fell in love with the anatomy. Everything that makes us human is concentrated in the head and neck: how we speak, swallow, smile, hear, and see one another. Serving that anatomy felt like serving the essence of people. The challenge—and privilege— of caring for patients as a surgeon while safeguarding these delicate functions has always inspired me.

Dr. Rapoport: You chose to pursue an MD/PhD. What inspired you to take this dual-degree path rather than a more traditional MD track?

Dr. Nguyen: I wanted to make an impact on a bigger scale. While I treasure the one-on-one interactions with my patients—one of my favorite surgeries is stapedectomy because of the tangible, immediate restoration of hearing it facilitates—I also felt a pull towards making a broader contribution. I had the curiosity and the patience for lab work, to see something new that no one had ever seen before. I wanted to discover something that could help many. I was fortunate to be accepted into the MD/ PhD program at Washington University in St. Louis, which had the experience and capability to nurture a physician– scientist with my goals. My time there was a defining period for me professionally.

Dr. Rapoport: Your early PhD work involved creating the first transgenic mice expressing fluorescent protein in neurons. What was that discovery like?

Dr. Nguyen: Magical. I was cutting facial nerves in tiny mice, then performing time-lapse imaging as they degenerated and regenerated. I was often alone in the dark, sometimes in the middle of the night, watching these glowing nerve branches search and grow. I remember thinking, “This is the first time anyone has ever seen this.”

Those “aha” moments live inside you forever.

They also planted the seed: If we could see nerves in mice, why couldn’t we illuminate them in humans?

Dr. Rapoport: Your work on fluorescent nerve imaging is fascinating. Can you tell us about your journey to that innovation?

Dr. Nguyen: It really began during my PhD in the 1990s. We were the first to create transgenic animals with green fluorescent protein (GFP) under a neuron-specific promoter. I was working on the facial nerve in mice, watching degeneration and regeneration in living animals through time-lapse videography.

When I came to UC San Diego, I had the opportunity to work with the late Dr. Roger Tsien, who would later win the Nobel Prize for his work on GFP. We developed a fluorescent peptide that, when injected, is cleaved by nerve-specific enzymes, causing it to fluoresce and essentially “paint” the nerves so they light up. This has incredible implications for surgery, where the visual field is often a narrow dynamic range from tan to red. Fluorescence in surgery adds a whole new dimension to operating, helping surgeons improve their ability to identify and preserve critical nerves.

Dr. Rapoport: The path of a surgeon– scientist is undoubtedly challenging. How important was mentorship in your career, especially in balancing clinical work and research?

Dr. Nguyen: Mentorship was, and remains, incredibly valuable to me. I was very fortunate to have Dr. Jeff Harris as my chair at UC San Diego for the majority of my career. He has been a steadfast supporter and sponsor, providing me with the flexibility and protected research time to pursue my ideas. He supported me through a K award and my first RO1 grant, and he had the patience to wait for my projects to come to fruition. That has been the greatest gift.

Working with Dr. Tsien was also a formative experience. He had a brilliant, animated mind. He would visualize molecular structures in three dimensions that he would draw you into, so that you, too, could relate to this microscopic world. He made learning joyful and taught me the importance of understanding things at a fundamental level.

Dr. Rapoport: What is your vision for Bevonescein, the nerve-illuminating drug now undergoing human studies?

Dr. Nguyen: I want it to become standard-of-care—and accessible everywhere. The drug is infused into a patient’s intravenous fluids before surgery. Then, once they have exposed the operative field, surgeons can use a blue excitation light and a simple filter to visualize the nerves with Bevonescein. You don’t need an $800,000 Da Vinci robot or a $1 million microscope. A headlight and loupes are enough.

That accessibility matters for global surgery, for resource-limited settings, for democratizing safety.

One of my favorite serendipitous moments: The drug is water-soluble, so urine fluoresces! In abdominal surgery, when Bevonescein is used, you can actually see ureteral peristalsis as a moving wave of light. Urologists and colorectal surgeons love it.

Dr. Rapoport: Looking back on your journey, what is a defining piece of advice you would give to young physicians and aspiring surgeon–scientists?

Dr. Nguyen: I would say that staying clinical is critical. It’s what motivates you. It constantly reminds you why you are doing what you are doing. I had a patient once who wrote me a note that said, “I know that the number of patients you’ll operate on is finite, and I feel really fortunate that I’m one of them.” This idea touched me deeply. Our impact—clinical or scientific—is finite. We have to choose where we want that impact to land and organize our lives around that.

It’s also important to understand that the path to your goal is not always straight. You have to be brave enough to say, “I’m going there,” but be open to the fact that the direct path may not be the right one. Failures are opportunities to learn and to see what else is happening. My PhD advisor gave me a book called “The Path is the Goal.” The journey is what’s important. If you do it with grace, conviction, and a belief in why you’re doing it, you will make your impact. I hope everyone asks themselves, “Who do I want to impact?” and then structures their time, life, and effort to make sure they achieve that.

Dr. Rapoport is an attending physician in otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, D.C., and is an assistant professor at Georgetown University in the department of otolaryngology.

Dr. Rapoport is an attending physician in otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, D.C., and is an assistant professor at Georgetown University in the department of otolaryngology.

Leave a Reply