SAN DIEGO—The cancer field is rich with registry data on lung cancer, breast cancer, and other types of cancer, but there is no such data available for squamous cell and basal cell carcinoma of the head and neck. This leaves a limited evidence base for learning how to identify a high-risk case and how to choose treatments accordingly, an expert said here during a panel discussion at the Triological Society Combined Sections Meeting.

But enough data from the literature is available to give some guidance, said Timothy Johnson, MD, professor of dermatology and otolaryngology-head and neck cancer at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He encouraged clinicians and surgeons to run through a checklist of factors when they see these lesions.

Risk Determines Approach

In basal cell carcinoma, the most high-risk areas for subclinical extension and local recurrence are anywhere on the face other than the middle-risk areas of the cheek, forehead, scalp, and neck, according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. Lesions in those middle-risk areas become high risk if they are 10 mm or bigger, and low risk if they’re smaller than that, Dr. Johnson said. Other risk factors are recurrent lesions, lesions with the aggressive growth or micronodular histologic patterns, neurotropism, a site of prior radiation, immunosuppression, and poorly defined borders.

“When I look at a basal cell, I ask myself (about) these eight factors,” he said. “The majority of basal cell skin cancers are small, low-risk lesions.” Most can be treated with excision, radiation or curettage, and electrodessication, he said, with cure rates on par with Mohs surgery.

“But when you start seeing more of these factors, you need to start considering Mohs surgery,” Dr. Johnson said. “Or, if you’re going (to do) standard incision, consider wider margins and deeper margins.”

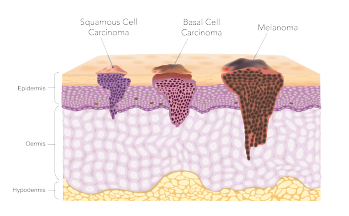

Squamous cell carcinoma involves the same locations, tumor sizes, and other considerations as basal cell when it comes to assessing risk. Clinicians also should consider tumors to be high risk when they are 2 mm or greater in thickness, or they penetrate through the bottom layer of the dermis into fat. Tumors arising from radiation, those with rapid growth, and chronic inflammation such as an ulcer or a burn scar are also high-risk lesions, he said.

The majority of basal cell skin cancers are small, low-risk lesions. —Timothy Johnson, MD

Dr. Johnson said when many of these risk factors are present, he considers a sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging.

Mohs Surgery vs. Standard Excision

The only prospective randomized trial comparing Mohs surgery to standard excision for high-risk basal cell lesions found a difference in rate of recurrence that was not significant (4.4% vs. 12.2% for standard excision, p=0.100) in primary tumors, but significant in recurrent tumors (3.9% vs. 13.5%, p=0.023) (Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:3011-3020).

For squamous cell cancer, a meta-analysis found a difference in recurrence rate: 3% vs. 8% for primary tumors and 10% to 23% for recurrent tumors. In an analysis that included Mohs surgery, tumors 2 cm or less have been found to have a local recurrence rate of 2%, as compared with 25% for those 2 cm or greater (NCCN Guidelines Version 1. 2020. Squamous Cell Skin Cancer. Feb 18, 2020).

“How do you get your standard excision recurrence rate [to be] less?” Dr. Johnson said. “You need to look at those risk factors and treat more aggressively if you have a lot of risk factors.”

The Use of Free Flaps

© solar22 / SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

In another segment of the panel, Tamer Ghanem, MD, PhD, chief of head and neck surgery at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, said that free flaps can play a role in large defects when a local or pedicled flap isn’t feasible. But it’s an involved procedure that is high up on the “reconstructive ladder,” and is not one of the first considerations, he said. Because the procedure adds three to six hours to the surgery, clinicians and surgeons have to choose patients carefully.

“This is one of the most difficult parts,” Dr. Ghanem said. Physiologically, he said, “this is a fairly stressful procedure.” Patients with comorbidities might not be able to tolerate it, and the decisions might not be straightforward, he said.

Options for free flaps include the latissimus dorsi flap—the “workhorse” for large-defect scalp reconstructions, Dr. Ghanem said—as well as the radial forearm skin flap, anterolateral thigh flap, rectus abdominis muscle flap, sural flap, or a scapula or parascapula flap.

Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsies

The use of sentinel lymph node biopsy in non-melanoma skin cancers is still evolving, Dr. Ghanem said.

In one review of 53 patients who underwent a biopsy because of high-risk squamous cell carcinoma features, with adjustments for tissue processing and immunohistochemistry findings, the positivity rate was 15.1%, with a false omission rate of 7.1% (JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;142:1171-1176).

“So, it’s not great,” he said. “We are currently using sentinel node [biopsy] for early oral cavity squamous cell cancer. And there is probably a role in skin cancer.” But compared to scanning, it’s still just the “next best thing,” he said.

‘Symmetrize the Defect’

William Shockley, MD, chief of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, described a case that captured the finesse that can be needed for patients who have had a resection on the face. A 43-year-old woman had a defect from resection of squamous cell carcinoma in the middle of her upper lip. The defect extended into muscle tissue. Dr. Shockley chose to do an Abbe flap, involving the transfer of skin, muscle, and mucosa from the lower to the upper lip.

A principle he followed was to “symmetrize the defect,” which in this case meant moving the red part of the native lip more to the middle. This symmetry can help the final result look more natural.

The woman was happy with the result but asked for more of a Cupid’s bow, the classic double-curve shape of the upper lip. He kept this adjustment “really simple and low-risk,” he said, drawing out a new Cupid’s bow, excising skin and just advancing the vermillion of the lip—yielding a striking before and after.

Dr. Shockley said that, in his view, facial and nasal contours, and the position and orientation of special facial structures, are more important than nasal or facial scars. Sometimes, he added, symmetry is not as vital as you might think. It’s far more crucial for the nose, say, than the ear.

“Symmetry is important,” he said. “But it is less important as you move away from the midline.”

Thomas Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.