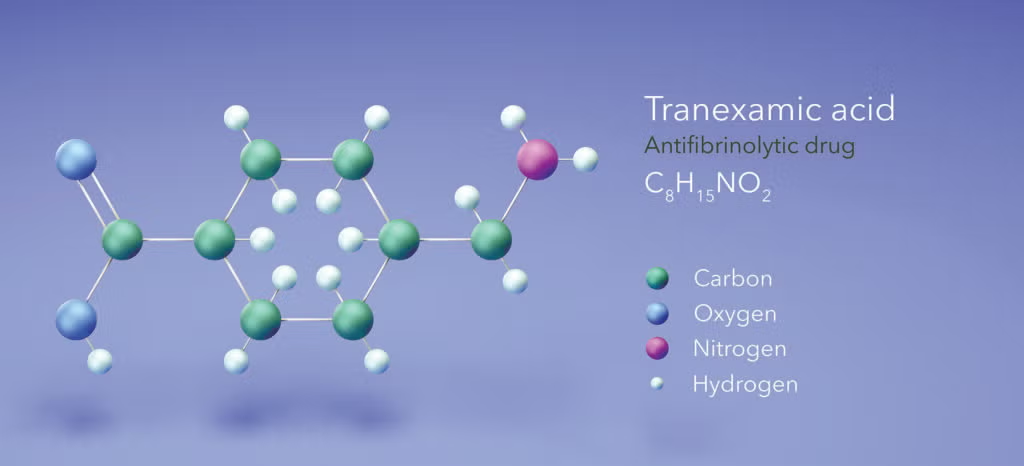

A growing number of otolaryngologists are now using tranexamic acid (TXA) to reduce intraoperative and postoperative bleeding. As a synthetic analog of the amino acid lysine, TXA promotes anti-fibrinolysis by binding to the lysine-binding sites on both plasminogen and plasmin, whereby attachment to fibrin is prevented and activation of plasminogen to plasmin and subsequent fibrin degradation by plasmin is precluded. Administered either intravenously or orally, TXA has a 30%-50% oral bioavailability and a relatively short half-life of two to three hours (World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. doi: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2020.05.010).

A growing number of otolaryngologists are now using tranexamic acid (TXA) to reduce intraoperative and postoperative bleeding. As a synthetic analog of the amino acid lysine, TXA promotes anti-fibrinolysis by binding to the lysine-binding sites on both plasminogen and plasmin, whereby attachment to fibrin is prevented and activation of plasminogen to plasmin and subsequent fibrin degradation by plasmin is precluded. Administered either intravenously or orally, TXA has a 30%-50% oral bioavailability and a relatively short half-life of two to three hours (World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. doi: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2020.05.010).

Explore This Issue

December 2025Used off label, the antifibrinolytic agent is increasingly being used both in pediatric and adult otolaryngologic procedures. Its adoption in otolaryngology, as well as many other surgical specialties, comes from the strong evidence collected in emergency medicine, where TXA has long been adopted and well studied. Based on the current evidence, the National Association of EMS Physicians, the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, and the American College of Emergency Physicians published a recent joint position statement in 2025 in the Annals of Emergency Medicine (see Recommendations for TXA Use below), in which they offer recommendations for TXA in the emergency room setting and offer resources and evidence to support their position (Transfusion. doi: 10.1111/ trf.17779).

In orthopedic surgery, evidence to date comes from two large meta-analyses, one that shows its efficacy in reducing peri-operative blood loss and requirements for transfusions without significantly effecting thromboembolic complication risk, and another looking specifically at the safety of TXA in major orthopedic surgery and showing no significant increase in venous thromboembolism (J Orthop Trauma. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000913; Blood Transfus. doi: 10.2450//2017.0219-17).

Although most uses of TXA are off label based on this evidence, recently the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved its use in specific situations: in the postpartum setting to reduce the risk of life-threatening bleeding, and prophylactic use for dental procedures in patients with hemophilia (In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. PMID: 30422504. Lancet. doi: 10.1016/ S0140-6736(24)02102-0).

While there is a paucity of evidence-based medicine specifically in the use of TXA in otolaryngology, the strong safety profile of TXA documented in the emergency setting and orthopedic surgery literature, as well as anecdotal evidence from the many otolaryngologists who use it in practice, has made it clear that this agent is a useful tool for reducing or preventing blood loss for many adult and pediatric patients.

Leave a Reply