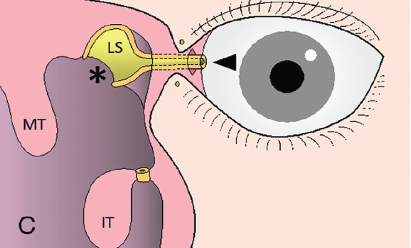

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the surgical findings of conjunctivoductivo-dacryocystorhinostomy. (IT = inferior turbinate; LD = lacrimal duct; LS = lacrimal sac; MT = middle turbinate.) Here, the tip of the severed nasolacrimal duct is withdrawn into and sutured to the conjunctiva incision (arrowhead). The medial wall of the lacrimal sac is trimmed and the lacrimal sac is widely opened (asterisk).

Explore This Issue

January 2022© Ushio M, et al. Laryngoscope. doi:10.1002/lary.29861

Introduction

Tear fluid enters the lacrimal sac from the upper and lower punctum at the medial canthus through the superior and inferior canaliculi and then flows through the nasolacrimal duct into the nose. Obstruction in any part of the abovementioned lacrimal passage is the most common cause of epiphora, also known as excessive watering of the eye. Epiphora can be symptomatic of other underlying conditions and affects the quality of life (QOL) of patients.

Canalicular obstruction can occur in either the upper or lower canaliculi; when both are obstructed, the tear fluid is not secreted from the nasolacrimal duct toward the nose, resulting in epiphora. Although the cause of canalicular obstruction is unknown in many cases, it may be influenced by aging, trauma, tumors, and oral anticancer medication.

The first response is to enlarge the canaliculus by inserting a silicone tube, a surgical procedure commonly known as canaliculoplasty; however, the placement of a Jones tube or canaliculi-dacryocystorhinostomy with an external incision is only considered when the canaliculus is reoccluded or cannot be kept open (Am J Ophthalmol. 1965;59:773-783; The Lacrimal System. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996:297-302).

Jones tube placement, first reported in 1965 (Am J Ophthalmol. 1965;59:773-783), is the gold standard for treating canalicular obstruction; it includes the semi-permanent placement of a glass tube through the medial canthus into the nasal cavity. One problem associated with this procedure is the need to implant a foreign body in semi-permanent detention. Lifelong hospital visits to clean and replace the tube are therefore required. In addition, complications such as eye pain, dry eye, foreign body sensation, infection, mechanical strabismus, diplopia, positional abnormalities, prolapse, and implantation may also occur in some cases.

Canaliculo-dacryocystorhinostomy (The Lacrimal System. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996:297-302) is performed with an external incision of approximately 2 cm on the side of the nose, thus leaving a scar. Additionally, the surgery is complicated and the infrastructure necessary to perform it is limited.

The treatment of canalicular obstruction is essential in improving the QOL of patients. However, there is no nonexternal incisional surgery that does not require the insertion of a foreign body to treat intractable canalicular obstruction, as opposed to endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy, which is a nonexternal incisional surgery for nasolacrimal duct stenosis (The Lacrimal System. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996:297-302). To address the aforementioned issues, we introduce a novel method, conjunctivoductivo-dacryocystorhinostomy, for anastomosis of the conjunctiva and nasolacrimal duct without leaving any facial scars or foreign bodies in semi-permanent detention.

Method

A 39-year-old male and a 54-year-old female presented to our clinic with intractable obstruction of the left canaliculus, for which they had undergone canaliculoplasty several times at another clinic. They had undergone sheath-guided endoscopic probing (SEP) and sheath-guided intubation (SGI) at our clinic, but the left canalicular opening was not maintained.

We performed lacrimal syringing to assess the patency of the lacrimal passages by flushing a saline solution through the lacrimal punctum to check how well it was draining. SEP and SGI were performed when occlusion was confirmed in the upper and lower canaliculi. Occlusion was confirmed in the upper and lower canaliculi even after SEP and SGI.

Surgical Technique: We performed all surgical procedures under general anesthesia. First, we created a mucosal flap with the upper end 8 to 10 mm above, the anterior end 10 to 12 mm ahead of, and the lower end 18 to 20 mm below the axilla of the middle turbinate.

After the lacrimal bone junction was confirmed, the frontal processes of the maxilla and lacrimal bone were removed. We exposed the entire nasolacrimal duct and lacrimal sac. Mucous nasolacrimal duct and lacrimal sac were then dissected from the bony nasolacrimal canal and orbital periosteum. The upper end of the lacrimal sac was left without detaching it from the orbital periosteum. The nasolacrimal duct was severed at the lower end as far as possible.

We introduce a novel method for anastomosis of the conjunctiva and nasolacrimal duct without leaving any facial scars or foreign bodies in semi-permanent detention.

At the medial canthus, the transition from the eyelid to the ocular conjunctiva beside the lacrimal caruncle was incised. A pair of hemostatic forceps were moved in the direction of the orbital periosteum through Horner’s muscle, where the lacrimal sac was detached from the conjunctival incision, and the orbital periosteum was perforated at the tip of the forceps. The end of the severed nasolacrimal duct was grasped by the forceps and withdrawn from the conjunctival incision. The trimmed end of the nasolacrimal duct and the conjunctival incision were sutured with 8-0 absorbent sutures to form a new lacrimal punctum.

We inserted one end of a PF catheter through the new lacrimal punctum. The medial wall of the lacrimal sac was reconfirmed at the tip of the PF catheter and trimmed, and the lacrimal sac was opened wide. The PF catheter was threaded through a bead with a diameter of 4 mm to secure it to the eyelid conjunctiva at the medial canthus, and the other end of the catheter was inserted through a new lacrimal punctum. We covered the exposed bone with the mucosal flap created at the beginning, taking care not to close the lacrimal sac orifice.

The PF catheter was removed after confirming that the mucosa around the lacrimal sac orifice, as well as the newly created lacrimal punctum, had epithelialized three to four months postoperatively.

Results

After surgery, the newly made punctum at the left medial canthus was maintained. Tear fluid stained with fluorescein and observed to be yellow-green under blue light decreased. The patency of the lacrimal passages was confirmed via lacrimal syringing. The new lacrimal passage was then maintained and had not reoccluded at a follow-up more than a year after removing the PF catheter in both patients.

View the video of the technique described here.