INTRODUCTION

Complex laryngotracheal stenosis remains challenging to treat. Although various endoscopic and open surgeries can treat posterior glottic stenosis, failures can occur. Open surgery using cricoid cartilage grafting, cricotracheal resection (CTR), and stenting has been effective in pediatric patients; however, in adults, these techniques often result in graft loss, granulation tissue, and restenosis.

Expansion laryngoplasty (EL) is an open surgical procedure for patients with combined glottic and subglottic stenosis. It combines unilateral arytenoidectomy with cricoid expansion by grafting to provide hard and soft tissue expansion. EL allows for soft tissue coverage of the graft with a pyriform sinus flap through arytenoidectomy. This soft tissue coverage allows for airway enlargement with both hard and soft tissues.

METHODS

Study Design

This study was approved by the Mount Sinai Hospital Institutional Review Board. This retrospective review of a single-surgeon (PW) experience included all patients with glottic and subglottic stenosis who underwent EL from 2006 to 2021. Operative events, demographic information, voice and swallowing outcomes, and decannulation rates were recorded.

Operative Procedure

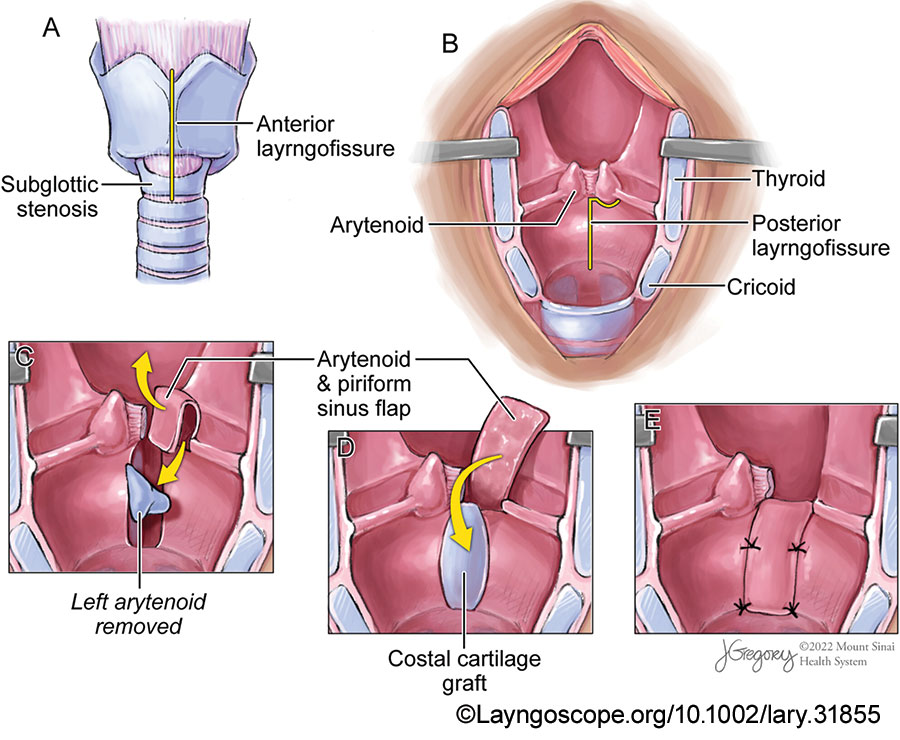

Figure 1: Expansion laryngoplasty steps: laryngofissure, arytenoidectomy, and reconstruction with costal cartilage graft and pyriform sinus flap. (A) A standard anterior laryngofissure is made in the midline to split the thyroid and cricoid cartilages. (B) The larynx is retracted open, and the cricoid is split posteriorly along with the posterior glottic stenosis in the interarytenoid space. (C) The arytenoidectomy is performed, but care is taken to preserve the arytenoid mucosa in what will become an anteriorly based piriform sinus flap. (D) The costal cartilage is inserted where the posterior cricoid split has been made and held in place by tension, then covered by the piriform sinus flap. (E) The pyriform sinus flap and cartilage are sutured in place to secure to reconstruction.

The surgery is divided into five main parts (Fig. 1):

- Rib cartilage harvest

- Laryngofissure and cricoid split

- Unilateral arytenoidectomy

- Pyriform sinus flap rotation and cartilage grafting

- Laryngeal stenting

A. Rib cartilage harvest: The procedure begins with a right-sided costal cartilage harvest. A costal cartilage graft of 3 cm × 1 cm × 0.5 cm is harvested. The design of the cartilage graft is similar to that described by Rutter and Cotton for pediatric stenosis. Briefly, a boat-shaped wedge of cartilage is harvested carefully to keep the periosteum on one surface.

B. Laryngofissure and cricoid split: A transverse incision is made, and cervical skin flaps are raised. The strap muscles are divided along the midline and retracted laterally. The tracheotomy site is evaluated and moved lower in the trachea if necessary. The perichondrium of the thyroid cartilage is then divided into the midline, and perichondrial flaps are preserved.

An oscillating saw is used to create the anterior laryngofissure through the thyroid and cricoid cartilages. The laryngofissure is completed using a #12 blade to incise the laryngeal mucosa without detaching either vocal fold from the thyroid cartilage (Fig. 1A). The posterior glottic scar and mucosa are divided sharply, followed by the splitting of the posterior cricoid ring. The lysis extends through the interarytenoid space and cuts the interarytenoid muscle (Fig. 1B). Subsequently, a complete split of the posterior cricoid ring is performed, and the cricoid ring is expanded to allow insertion of the costal cartilage graft.

C. Unilateral arytenoidectomy: Following the cricoid split and posterior commissure scar lysis, an arytenoidectomy is performed (Fig. 1C). Before surgery, the vocal fold with the least mobility or with the least favorable position is identified, and the arytenoid on that side is planned for resection. The mucosa overlying the arytenoid is carefully preserved by performing a submucosal arytenoidectomy. This mucosa becomes the pyriform sinus flap for coverage of the cricoid graft.

D. Pyriform sinus flap rotation and cartilage grafting: The pyriform sinus flap is created on the arytenoidectomy side by a releasing cut of the aryepiglottic fold laterally and a cut through the post-cricoid mucosa. This flap is cut to the level of the vocal fold. These cuts create a pedicle of arytenoid and medial pyriform sinus flap from the side of the arytenoidectomy. This mucosal flap is typically 2.5 cm in length and 1 cm in width. The flap is then rotated downward into the posterior lumen of the larynx to cover the costal cartilage graft (Fig. 1D). The mucosal flap must rotate to the bottom of the cricoid cartilage without tension. The superior height of the flap should not be lower than the opposite vocal fold.

The cartilage graft is placed into the field and fits into the posterior cricoid split defect. It is sutured in place with 4-0 Vicryl sutures, with the perichondrial side facing the airway lumen. The pyriform sinus flap is rotated down and secured with a Vicryl suture to cover the costal cartilage. Fibrin glue is then used (Fig. 1E).

Leave a Reply