The number and type of in-office rhinology procedures continue to grow and expand, with more otolaryngologists incorporating these procedures into their practices. Technological advances, availability of local and topical anesthetics, good outcomes in terms of efficacy and safety, physician familiarity and comfort with doing the procedures on an awake patient, improved patient experience and reduced cost, and a general trend in medicine toward patient-centered care all contribute to this growth.

The number and type of in-office rhinology procedures continue to grow and expand, with more otolaryngologists incorporating these procedures into their practices. Technological advances, availability of local and topical anesthetics, good outcomes in terms of efficacy and safety, physician familiarity and comfort with doing the procedures on an awake patient, improved patient experience and reduced cost, and a general trend in medicine toward patient-centered care all contribute to this growth.

Explore This Issue

September 2025In a 2016 survey of American Rhinologic Society (ARS) members on practice patterns regarding office-based rhinology procedures, 63% of the respondents reported an increase in the number of office-based procedures they performed over the last five years. Published in 2019, the survey found that sinonasal debridement was the most commonly performed procedure (99%), followed by polypectomy (77%) and balloon sinus ostial dilation (56%). Some members also reported performing more complex procedures, including ethmoidectomies (35%), antrostomies (31%), sphenoidotomies (24%), frontal sinusotomies without the balloon (21%), and steroid-eluting sinus implants (30%) (Am J Rhinol Allergy. doi:10.1177/1945892418804904).

Since that survey, the list of new procedures introduced into and more widely used in the office setting has grown to include Eustachian tube balloon dilation, radiofrequency of the posterior nasal nerve, cryoablation of the posterior nasal nerve, radiofrequency nasal valve remodeling, and nasal valve implantation, according to Jivianne T. Lee, MD, professor of rhinology and endoscopic skull base surgery in the department of head and neck surgery at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and the ARS vice president who led the 2019 survey. The biggest advances, she said, are in the arena of chronic rhinitis, where new technologies and devices, such as temperature-controlled radiofrequency ablation and cryoablation, permit in-office treatment.

Patient selection is critical. Those who have a lower pain tolerance and/or have anxiety with medical procedures would not be ideal candidates and would probably be best served by undergoing general anesthesia. —Jivianne T. Lee, MD

“There is no question that the office armamentarium has expanded considerably since 2019,” she said. “It is so incredible how there’s been a renaissance of technology and advances where we can treat some of these conditions in the office setting.”

She added that in-office procedures have become so common that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has assigned specific procedure codes over the past couple of years.

A more recent survey published in 2024 adds further data on the growth of in-office rhinology procedures internationally (Surgeries. doi.org/10.3390/surgeries5020039). Conducted by collaborators in the Rhinology section of the Young Otolaryngologists of International Federation of Oto-rhino-laryngological Societies (YO-IFOS), the survey showed that among 172 otolaryngologists from 26 countries who responded, the list of in-office rhinology procedures ranged from the simpler, more commonly performed procedures, like polypectomy and turbinate reduction/turbinectomy, to increasingly more complex and less commonly performed procedures like Eustachian tuboplasty, septoplasty/caudal deviation, sphenoidotomy, and frontal sinus surgery.

Advantages and Risks

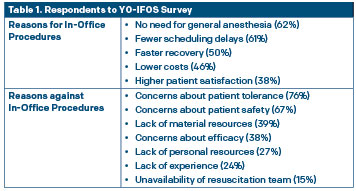

The shift to performing more rhinology procedures in office versus in an operating room is driven by a number of advantages, but surgeons and patients need to be aware of potential risks. Respondents in the 2024 survey listed the key reasons to consider when deciding whether to do a procedure in the office (Table 1).

The shift to performing more rhinology procedures in office versus in an operating room is driven by a number of advantages, but surgeons and patients need to be aware of potential risks. Respondents in the 2024 survey listed the key reasons to consider when deciding whether to do a procedure in the office (Table 1).

David W. Jang, MD, associate professor and division chief of rhinology and endoscopic skull base surgery at Duke University in Durham, N.C., underscored the benefits for patients—avoiding the risks of general anesthesia and reducing out-of-pocket expenses—and for practitioners—having a flexible operating schedule versus having to rely on a hospital or surgery center’s schedule.

He emphasized, however, that longer and more complex surgeries, like frontal sinusotomy, are better done under general anesthesia in the operating room to maintain safety and ensure optimal outcomes.

If an in-office procedure is considered, he said he ensures that an emergency plan is in place in case of complications. “For example, staff will have equipment and supplies ready in case of severe bleeding, and there will also be a protocol to call EMS and transport patients to a nearby hospital that is equipped to handle ENT emergencies,” he said.

In addition, he emphasized the need to assess bleeding risk when considering an in-office procedure. “Bleeding can be difficult to manage in the office, especially in an awake patient,” he said, adding that patients with poor lung function are also at high risk because bleeding can lead to aspiration.

Noting that bleeding is always a risk with sinus surgery, William C. Yao, MD, associate professor, chief of rhinology and anterior skull base surgery, and residency program director of the department of otorhinolaryngology–head and neck surgery at UT Health Houston–McGovern Medical School, pointed out that the risk of bleeding is actually lower without the use of general anesthesia. “With the use of local anesthesia, we are able to avoid one side effect of general inhalational anesthesia, which is vasodilation leading to increased bleeding,” he said. He said he has cautery devices in the office in case of bleeding.

Dr. Lee underscored a key advantage of in-office procedures: reduced recovery time for the patient. “For most of these cases, patients only have to take the day off for the procedure and no additional time,” she said. “It is becoming similar to going to the dentist, where you receive a shot of local anesthesia, have the procedure done, and resume your normal activities by the next day.”

For Dr. Lee, the main risk is patient discomfort. “Patient selection is critical. Those who have a lower pain tolerance and/or have anxiety with medical procedures would not be ideal candidates and would probably be best served by undergoing general anesthesia,” she said.

Patient Selection, Anesthetic Use, Managing Awake Patients

Although the type of procedure largely determines suitability for the in-office setting, patient selection is a close second. Edward D. McCoul, MD, MPH, the director of rhinology and sinus surgery in the department of otorhinolaryngology at Ochsner Health System in New Orleans, said a key criterion he uses for patient eligibility is how well a patient tolerates diagnostic nasal endoscopy. “If a patient is wincing or grimacing or has a vasovagal reaction during a basic 30-second endoscopy, that patient is probably not a good candidate for an in-office procedure,” he said.

It is possible to make a person comfortable even if you’re sticking things into their nose, as long as you avoid unnecessary contact with the walls of the nose and don’t apply unnecessary force, and also be mindful that the nose is still attached to a person — Edward D. McCoul, MD, MPH

Leave a Reply