Repeat operative or clinic-based procedures to debulk papillomatous disease have been the standard of care to date in the treatment of patients with recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP) caused by chronic infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) type 6 or 11. Treatment of RRP is one of the rare instances in medicine of a chronic infection treated with repeat procedural intervention.

Explore This Issue

May 2025Although the development of powered microdebriders and angiolytic lasers has certainly improved the precision of procedural intervention and thus improved voice outcomes after procedures, operative intervention itself leads to iatrogenic laryngeal injury that causes scarring, dysphonia, and possibly airway obstruction in many patients. I’ve cared for many patients whose larynx has been reduced to a dysfunctional bed of scars by very well-meaning surgeons. The desire of RRP patients to stay out of the OR, combined with the inherent risk of procedures, has led the field to search for safe and effective noninvasive medical treatments aimed at addressing the underlying cause of the disease.

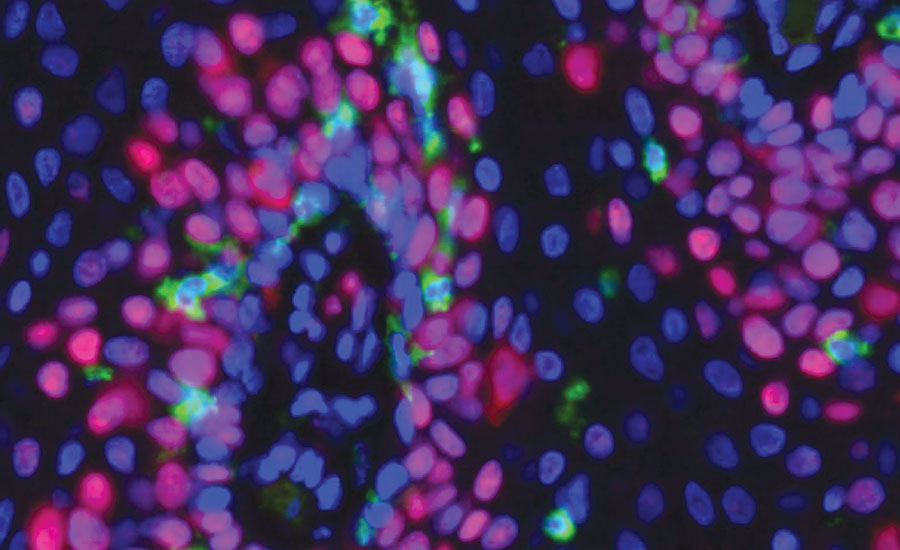

Representative immunofluorescence imaging (40X) showing green CD8+ T cells infiltrating papilloma tissue. Nuclear are stained blue, and proliferating cells are stained red. Photo credit: Dr. Clint Allen

Recent hope for such a medical treatment came with very promising results observed with the use of bevacizumab to block the formation of new papilloma blood vessels. Systemic administration of bevacizumab can lead to impressive disease control in patients with severe, bulky papilloma throughout the larynx and trachea. Although it is a powerful treatment option, prospective trials and retrospective case series have demonstrated that stopping bevacizumab treatment often leads to papillomatous disease recurrence, likely because the treatment does not address the underlying cause of the disease—chronic HPV infection. Additionally, for individual patients receiving bevacizumab, it is unclear how long treatment can continue before known side effects of treatment emerge. Collectively, RRP investigators hypothesized that immunotherapy specifically designed to activate the immune system against HPV could lead to durable disease control and even a cure.

The idea of trying to direct the immune system against papillomas in patients with RRP is not new. In fact, RRP was found to be caused by an “infectious agent” in the 1920s, long before the discovery of HPV itself. This observation eventually spurred a series of clinical trials in the 1960s in which laryngeal papillomas were resected, pulverized, and subcutaneously injected back into patients as an “autologous vaccine,” despite these investigators not knowing that the infectious agent was a virus.

These trials demonstrated variable efficacy but were never widely implemented for a number of practical reasons. In the late 1970s into the early 1980s, chronic HPV infection was determined to be the direct cause of RRP by Harold zur Hausen (who won the Nobel Prize for his observation that HPV causes cervical cancer) in Germany and Haskins Kashima at Johns Hopkins. This discovery spurred a new round of clinical trials in the late 1980s attempting to activate the immune system against HPV by subcutaneously injecting the immune-stimulating cytokine interferon. Variable efficacy and significant side effects were observed in these studies, again limiting the use of this therapy in RRP patients.

In the 30 or so years since these interferon trials, excellent research clearly demonstrated that the immune response present within RRP clinical specimens was dysfunctional and needed help, but not much immunotherapy research aiming to boost the immune response for RRP patients took place. Yet, science was not still, and major advances in our understanding of how to activate immune responses against cancer were occurring.

RRP investigators benefited from these advancements and, beginning about five years ago, clinical trials investigating immunotherapy for RRP resumed, using some of the tools developed to boost anti-cancer immunity. The first of these trials, conducted separately at the National Institutes of Health and Harvard University, used an immunotherapy strategy called immune checkpoint blockade. This treatment, now widely used in many cancers, including head and neck cancer, blocks signaling through the programmed death receptor/ligand (PD-1/L1) axis and reverses one of the ways that tumor-specific immune cells can be turned off when they enter a tumor. This treatment can be very powerful, but is generally nonspecific and carries the risk of activating the immune system against something important other than the tumor. Papilloma shrinkage and stabilization of disease were observed in some but not all of the patients treated in these trials, and no patients experienced complete elimination of disease. Combined with the risk of developing a serious immune-related side effect from treatment and the lack of observed robust clinical responses in most patients, some RRP investigators felt that safer and more specific immunotherapy was needed.

This directly led to the idea that immunotherapies specifically designed to activate HPV-specific immune responses may be safer and more useful in RRP. Similar HPV-specific immune treatments had already been designed and were already being tested in patients with HPV-associated cancer.

Over the last four years, two separate DNA immunotherapies from two different companies have been developed and have undergone initial safety and efficacy testing in adults with RRP. PRGN-2012 from Precigen, Inc., is a viral vector-based treatment where a replication-incompetent virus containing a DNA payload designed to activate immune responses against HPV 6 and 11 is administered subcutaneously in the adjuvant setting after surgical papilloma debulking. With the PRGN-2012 product, the virus does the work of delivering the portions of HPV to the immune system to induce HPV-specific immunity. INO-3107 from Inovio is an HPV 6 and 11 DNA product administered intramuscularly that enters immune cells to activate HPV-specific immunity with the use of externally applied electroporation delivered with a handheld device. Both treatments aim for the same outcome—to activate HPV 6 and 11-specific immune responses of sufficient magnitude to prevent regrowth of papillomatous disease after standard-of-care surgical papilloma cleanout.

The results from phases 1 and 2 from both products have been impressive. In both studies, fewer interventions were required in the year after the study treatment compared to the year before in most patients, and responses were durable for most patients. I encourage all to read these two studies (Lancet Respir Med. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(24)00368-0; Nat Commun. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-56729-6) to understand specific differences in study design, treatment details, and clinical outcomes—and there are differences.

Importantly, laboratory correlative studies from both studies have demonstrated that the treatments do what they are supposed to do—activate HPV 6 and 11-specific immunity. Given these impressive results in a disease with no other approved treatment options, and the outstanding safety profiles observed with both products, both the Precigen and Inovio treatments have been awarded Breakthrough Therapy designation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and both companies are moving forward with the steps required for the FDA to consider these agents for Accelerated Approval.

At long last, we are close to the goal of shifting the primary treatment of RRP from procedural debulking to disease control with safe, noninvasive medical treatment. The observed efficacy of systemic bevacizumab (while on treatment) and new DNA immunotherapies mean there will be treatment options that must be carefully considered.

Certainly, once one or both DNA immunotherapies gain FDA approval for commercial use, clinical and research leaders in the RRP community will gather and produce workup and treatment recommendations or guidelines for adults with RRP. Important questions, such as which treatment to use first and how to rationally combine treatments, remain.

Translation of these treatment options to pediatric populations will require more thoughtful work, but thankfully, this is becoming less imperative as the incidence of new pediatric RRP cases across developed countries, including the U.S., is plummeting with increased penetrance of preventative HPV vaccination.

Otolaryngologists will always be the primary caretakers for patients with RRP since we have the expertise to monitor disease status and procedurally intervene for papilloma debulking when necessary. And debulking procedures will undoubtedly still be required for some patients; however, with the widespread availability of these new systemic treatments, the care of adults with RRP will naturally shift from otolaryngology alone to a multidisciplinary collaboration between otolaryngologists and medical oncologists, similar to head and neck cancer care. Implementation of such multidisciplinary teams that can offer all treatment options for adults with RRP will more easily occur initially in academic medical centers, but with experience in use and accumulation of real-world results, these treatments should be widely used by all who care for patients with RRP.

While performing a long papilloma debulking operation in my fellowship, my mentor, Dr. Merati, said to me, “Someday we will figure out how to get the immune system to go after the HPV infection—and none of these poor patients will have to come to the OR anymore.”

Dr. Merati, we are so close!

Dr. Allen is the senior investigator in the Surgical Oncology Program for the Center for Cancer Research at the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, in Bethesda, Md.

Dr. Allen is the senior investigator in the Surgical Oncology Program for the Center for Cancer Research at the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, in Bethesda, Md.

Leave a Reply