Younger physicians and surgeons may be more susceptible to developing burnout, perhaps in part because they have not yet developed appropriate experience and coping mechanisms. Indeed, it is estimated that up to 50% of medical students exhibit signs or symptoms of burnout at some point in their undergraduate medical career (Bull Am Coll Surg. 2011;96:17–22). This may well carry into residency training, and might even be exacerbated by increased educational and clinical pressures and decreased personal recovery time. Residency training is a time of highly accelerated acquisition of knowledge and skills and includes challenges in time management and wide-ranging experiences. Particularly in the surgical specialties, each resident physician brings to the training experience an abundance of intellectual and technical skills, cultural and family experiences, biases and perspectives, and personality traits. For surgeons, a healthy dose of obsessive/compulsive behavior is felt to be necessary, with perfectionism often a goal, even when these behaviors can occasionally reap negative results.

Explore This Issue

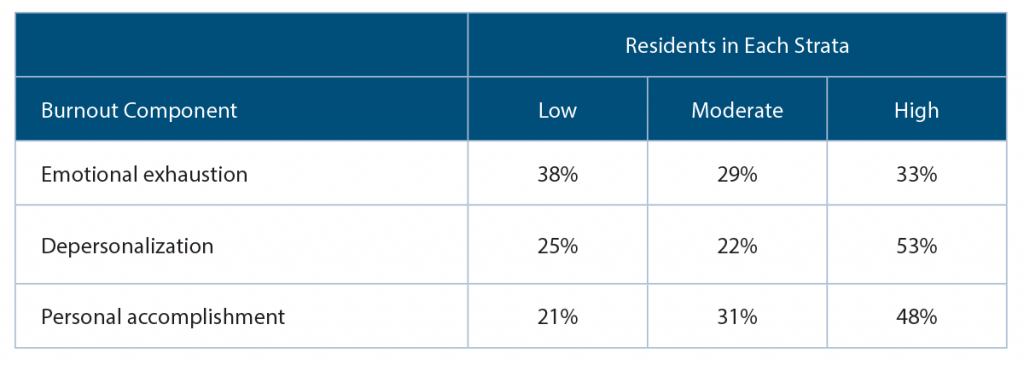

April 2017One of the best studies performed to date on burnout in otolaryngology residents was a survey published in 2007 by Golub and colleagues (Acad Med. 2007;82:596–601). The survey results were based on the responses of 514 otolaryngology residents in the second through fifth years of training. The authors reported an 86% response rate for residents reporting moderate (76%) or high (10%) levels of burnout at some time during their residencies (See “Maslach Burnout Inventory–Human Services Study Subscale Stratification of Otolaryngology Residents,” below). Interestingly, high levels of personal accomplishment seemed to buffer or protect against burnout.

If emotional exhaustion is an early predictor for the development of some level of burnout, it seems reasonable that close observation of a resident physician for this phenomenon would be a salutary finding to prompt intervention and mitigation. When depersonalization of oneself and of the patient leads to diminished capacity for self-realization and concern for the patient, burnout is at a serious stage. What follows may be an obvious lack of concern for personal appearance and care, and for the care of and interaction with patients. Errors and mishaps in patient encounters may occur, and these may further depress the resident, leading to lowered feelings of self-worth and a downward spiral of competency. Bedside manner becomes worrisome.

(click for larger image) Maslach Burnout Inventory–Human Services Study Subscale Stratification of Otolaryngology Residents

n=514

Source: Acad Med. 2007;82:596–601.

Early Recognition

It is an ethical imperative for the program director—as well as all faculty members—to be aware of the burnout phenomenon, and to always be observant for signs of its occurrence. Better yet, programs need to institute, or strengthen, preventive programs that directly impact and mitigate the issues that can lead to burnout in residency. This may well begin with faculty training on the burnout phenomenon, both for their own welfare and to enable them to recognize the signs and symptoms (perhaps in themselves as well as in the residents). Faculty recognition of the insidiousness of professional burnout will provide a better sense of why it is important to prevent and/or ensure early mitigation of these representative personal difficulties—physical and emotional exhaustion, detachment from social interactions, poor patient communications, difficulties with personal relationships, decreased self-confidence and self-worth, mistakes in patient care, and signs of clinical depression, to name a few.