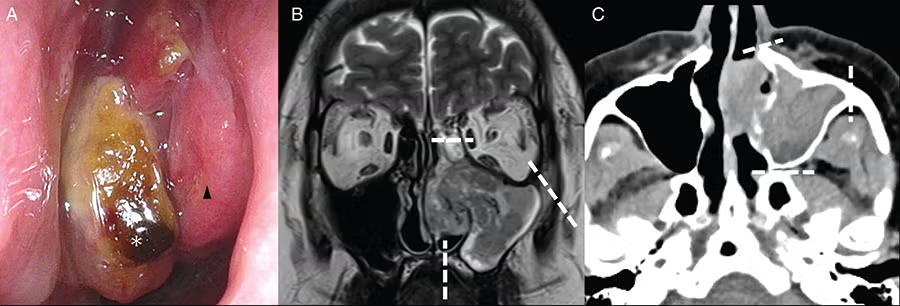

Figure 4: Pre-operative imaging findings of Case 3. (A) Left nasal findings. A tumor (asterisk) protruding from the maxillary sinus into the middle and common nasal passages was observed. The inferior turbinate (arrow) was identified. (B) Magnetic resonance imaging (T2-weighted image, coronal section). The tumor occupied the left maxillary sinus and partly protruded into a common nasal passage. The interior was heterogeneous, and there was no obvious destruction of the maxillary sinus bone. The medial orbital wall, hard palate, and zygomatic process were transected, as indicated by the white dotted line. (C) Computerized tomography (CT, horizontal section). Tumors were found in the maxillary sinus and partially connected to the nasal cavity. The nasal bone, zygomatic process, and pterygoid process were transected as the white dotted lines.

INTRODUCTION

Total maxillectomy is a surgical procedure involving amputation of the orbital floor, zygomatic bone, hard palate, and pterygoid process. It is typically performed in patients with cancer that has invaded the maxillary sinus. A common approach involves an external facial incision through a Weber–Ferguson skin incision; however, this method is associated with post-operative cosmetic complications. Furthermore, the conventional external incision approach is blind to the posterior and nasal sides of the maxillary sinus, which presents challenges in ensuring accurate margins. To compensate for these shortcomings, there are very few reports on endoscopically assisted surgery for advanced cancer of the maxillary sinus; however, there have been no reports of en bloc total maxillectomies in which a single tumor is resected without any facial skin incision. We developed a method for complete removal of the maxilla in cases of maxillary sinus cancer using an endoscopic technique that eliminates the need for facial skin incision. This technique ensures resection of the medial orbital wall and pterygoid process, which would otherwise be obscured by conventional methods.

Explore This Issue

June 2025In this study, three patients who underwent endoscopic maxillary surgery were examined. En bloc resection was successfully achieved in all three cases, with negative margins. The problem with endoscopic surgery is the difficulty in nasal manipulation; however, our co-authors have developed techniques to improve maneuverability. This study presents a pioneering report on an endoscopic total maxillectomy that allows for en bloc resection without a facial skin incision.

METHODS

Patients

Endoscopic total and subtotal maxillary sinus resection procedures were performed in three patients at Jikei University Hospital between April and October 2023. One patient with maxillary sinus cancer and two patients with oral cancer extending into the nasal cavity or maxillary sinus were included. Tumor location, stage, pathology, approach, surgical technique, and resection margins were comprehensively documented. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee (approval number: 34-102) and adhered to the ethical standards of the Human Experimentation Committee of Jikei University School of Medicine and the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 1983. We used an opt-out approach, and none of the patients refused consent.

All Instruments and Settings

We prepared a general nasal sinus endoscopic surgical instrument (Nagashima Medical Instruments, Tokyo, Japan). Endoscopic manipulation was performed using 4 mm rigid 0° and 70° endoscopes (Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan). When cutting the mucous membranes of the nose, we used a microneedle electrode with a total length of 14 mm (Muranaka Medical Instruments, Osaka, Japan). When drilling the maxillary bone, a Midas Rex drill system (Medtronic, Minneapolis, USA) with a diamond bur was used to cut the nasal bone and hard palate. When cutting the maxillary bone, we used a high-speed Primado2 bone saw (NSK, Tokyo, Japan). When reconstructing bone, we used the AO Matrix MIDFACE Preformed Orbital Plate (Synthes, Oberdorf, Switzerland). The intra-operative setting was also shown (Fig. 1).

Leave a Reply