The treatment of facial nerve paralysis and the operation of facial nerve centers are complex topics among those who treat these conditions. We spoke to the following facial plastic surgery otolaryngologists to get more information about the state of working with facial paralysis today:

- Babak Azizzadeh, MD, chairman and director of the CENTER for Advanced Facial Plastic Surgery in Beverly Hills, Calif.

- Laura T. Hetzler MD, director, Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center Facial Nerve Disorders Clinic in Baton Rouge, La

- Myriam Loyo Li, MD, MCR, co-director of the Facial Nerve Center at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland

- Matthew Q. Miller, MD, director of the University of North Carolina Facial Nerve Center in Chapel Hill

ENTtoday: Do you find treating patients with facial paralysis satisfying? If so, how?

Babak Azizzadeh, MD: Treating facial paralysis patients is extremely satisfying because of the profound impact on people’s quality of life with surgery and other modalities. Facial deformities can negatively impact a person’s ability to communicate and express their emotions to others, which can result in being ostracized by the rest of society.

Laura T. Hetzler MD: The current clinical practice of facial nerve disorders, ranging from paralysis to paresis to the aberrantly recovered, is an exciting and advancing field right now. One of the most rewarding situations is to meet a patient who’s been told for years that there’s nothing further that can be done. When they meet us, we can share that there are next steps and improvements that have developed within the last 10 years. It’s a field where we have really started pushing the envelope for outcomes, symmetry, and best practices.

Myriam Loyo Li, MD, MCR: Treating patients affected with facial paralysis is one of the best parts of my practice. Restoring the ability of a person to be able to move their face and to smile makes a dramatic impact on that person’s life. A lot of the surgeries we do take months to restore movement. When we start seeing movement for the first time, it’s wonderful. As a physician, we get to see the excitement in patients when movement starts to appear. As they gain facial strength, we get to watch our patients feel more confident in their appearance and smile more confidently. Knowing the treatment that I provided was able to make this happen for my patients is incredibly rewarding.

Matthew Q. Miller, MD: Working with and treating patients with facial paralysis is extremely satisfying; honestly, I cannot imagine a more satisfying career. Facial paralysis can be devastating for patients, and I’ve experienced this from both the provider’s and patient’s perspective, having been a facial paralysis patient myself.

Facial expressions have been called the “universal language,” and facial paralysis takes these expressions away. People often ignore what patients with facial paralysis are saying because they’re left wondering why they cannot make normal facial expressions. These experiences can leave patients feeling depressed and socially isolated.

When you work with facial paralysis patients as a provider, you develop a close relationship with them, as working to restore their facial form and function typically involves a long-term treatment plan. You must personalize the treatment plan depending on a patient’s goals, and no two patients are alike. Similarly, over time as patient’s goals change, your treatment plan may change. These close are extremely satisfying. Then, of course, helping patients smile again who haven’t smiled for years and sometimes decades is incredible.

Lastly, facial paralysis treatments combine aesthetic and reconstructive principles, perhaps more so than any other facial plastic and reconstructive surgical subspecialty. I love “borrowing” techniques I use in my aging face patients to improve results in facial paralysis surgery. Similarly, being a facial nerve surgeon makes me a better facelift surgeon.

ENTT: Is facial paralysis with slow onset often misdiagnosed as Bell’s palsy? If so, what else could a slow onset be a sign of?

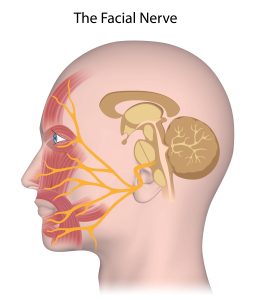

BA: Atypical presentations of facial paralysis, such as slow onset and weakness in various distributions of the facial nerve, are unfortunately so often misdiagnosed as Bell’s palsy. This is one area that we need to better educate emergency departments and primary care physicians. In my practice, metastatic cancer from a cutaneous or parotid origin is the most common cause of slow-onset facial paralysis.

LH: Understanding the onset and trajectory of facial nerve weakness is so important to accurate diagnosis. Bell’s palsy is typically a quicker onset, involving all branches of the facial nerve. Facial paralysis that’s irregular or progressive over weeks to months, is incomplete in its onset, or doesn’t recover is concerning for another cause outside of Bell’s palsy. I’ve seen slow onset with neuropathic, infectious, and inflammatory causes, but especially with benign or malignant tumors.

ML: Fortunately, I think misdiagnosis is rare, but it does occur. Bell’s palsy should only be flaccid for a maximum of six months. After that time, there can be synkinesis and residual weakness, but not complete flaccid paralysis.

Complete flaccid paralysis of greater than one-year of duration simply isn’t Bell’s palsy. A slow onset, and paralysis that affects only some branches of the face, is concerning for a tumor. Tumors can be benign or malignant and involve the base of skull (in particular, the cerebellopontine angle), the parotid, or the brain. Other causes of slow onset paralysis could be infectious, neurodegenerative, or even inflammatory, like Lyme’s disease or neurosarcoidosis.

MM: Facial paralysis is a manifestation of many different diagnoses. While Bell’s palsy is the most common cause of facial paralysis, patients are frequently misdiagnosed as having Bell’s palsy. Bell’s palsy and Ramsay Hunt Syndrome—both of which are caused by virus reactivation affecting the facial nerve—are always associated with sudden onset (within 72 hours) facial paralysis.

Gradual onset facial paralysis is never Bell’s palsy. Gradual onset facial paralysis can be a sign of either a benign or malignant tumor, or another less-common cause of facial paralysis. It’s very important that patients are evaluated by a provider familiar with facial paralysis to make sure the correct diagnosis is made, and appropriate treatment initiated.

ENTT: What gains have been made in caring for patients with an unsatisfactory recovery from facial paralysis?

BA: Over the past two decades, microsurgical free tissue transfer utilizing the gracilis free flap has become extensively used for patients with complete paralysis and Moebius syndrome. The other two surgical techniques that have also improved our treatment for facial paralysis are orthodromic temporalis tendon transfer and masseteric facial nerve transfer in combination with hypoglossal nerve transfer. In the past five years, modified selective neurectomy used to address post facial paralysis with synkinesis has gained significant importance. The use of neuromuscular retraining and nerve modulation has also improved due to better technical administration.

LH: Facial neuromuscular retraining, or FNMR, has been a remarkable advancement for patients suffering from synkinesis and hyperkinesis following paralysis. Surgeons who focus on facial nerve disorders have started taking a multidisciplinary approach to these patients, working with specially trained occupational therapists and physical therapists who perform FNMR. We’ve also refined patterns for botulinum toxin injections for synkinesis and have added direct myotomies of affected muscles (DAO and platysma) to our repertoire. In the last five-plus years, some of us have started to offer selective neurolysis for the muscles we typically treat with botulinum toxin.

ML: I think the most disappointing outcome is the failure of reinnervation or the failure to restore movement. Over the last decade, we have gained some critical insights to help prevent this. The masseteric nerve has become the most popular source of alternative neural input; it has minimal morbidity, requires a relatively simple surgery, and reinnervation has great success rates. We’ve learned to prioritize reinnervation of a midface branch rather than trying to reinnervate the entire facial nerve when using the masseteric nerve. We’re also understanding better how critical early reinnervation is.

Successful reanimation surgery with nerve transfer can have the problem of synkinesis, and we’re making great progress in treating synkinesis with physical therapy, chemodenervation, selective myectomies, and selective neurectomies. We’re also refining our free muscle transfers to make them less bulky in the face and design them in a way that lifts the corner of the mouth and the upper lip to create more natural smiles.

MM: Treatment for patients with facial paralysis has experienced a renaissance the last decade. There has especially been an explosion in treatment options for patients with chronic Bell’s palsy, chronic Ramsay Hunt Syndrome, and other causes of nonflaccid facial paralysis.

In nonflaccid facial paralysis, as the facial nerve recovers from an acute in-continuity nerve insult (e.g., Bell’s palsy, Ramsay Hunt Syndrome) it can regenerate to both appropriate and inappropriate facial muscles. This “aberrant facial nerve regeneration” creates an imbalance in facial muscles. For example, if the smile antagonist muscles (depressor anguli oris, buccinator) become stronger than a patient’s smile muscles (zygomaticus muscles), then a patient can be left with significant smile asymmetry preventing them from showing they’re happy. We now have procedures such as selective denervation surgery and depressor anguli oris excision that can rebalance the facial muscles and help patients smile again.

Over the last decade, our understanding of natural smile vectors and the importance of smile spontaneity has also led to innovations in treatments for patients with flaccid and nonflaccid paralysis, such as dual innervation and multivector free gracilis muscle transfer.

ENTT: How can the attitude of the surgeon/physician influence the way the facial paralysis patient sees themselves? Do statements like “It isn’t too bad” have an impact?

BA: Statements like, ‘It isn’t that bad,’ whether it’s coming from a physician or a family member, can absolutely have a negative impact on individuals with facial paralysis. Even minor facial asymmetries and smile dysfunctions can hurt a patient’s self-confidence, self-esteem, and self-perception. This is why physicians need to acknowledge the patient’s personal experience with facial paralysis and try their best to address it in the most empathetic and kind way.

LH: For any clinician who consistently sees patients with facial nerve disorders, we recognize how significant even subtle asymmetries can be to our patients. When I was in training just 15 years ago, we would have told any of these patients that they were fine and nothing more could be done.

Now, with FNMR, a better understanding of synkinesis patterns, and a range of therapeutic and surgical options, we can titrate an individualized plan for our patients. Sometimes, just sharing that there are options for improvement leads to tears of joy and hope.

ML: In my opinion, validating the patients’ lived experience is a very important part of caring for patients affected with facial paralysis. Close friends and family love the person no matter what and will often tell them it doesn’t matter how they look. While I do think this is true, our faces are a major part of how we interact with others.

In our current society, we struggle to interact with people with differences in facial appearances. It’s true that people with flaccid facial paralysis and with synkinetic facial paralysis are looked at differently than people with full facial movement. Humans have evolved to pay close attention to our facial expressions. Nonverbal communication is highly dependent on our facial expression. It’s hard to express joy with an asymmetric smile. I think the most disappointing outcome is failure of reinnervation or failure to restore movement.

As physicians, we now know that depression makes the experience of facial paralysis much worse, and that facial paralysis is associated with worse social anxiety. Acknowledging and treating depression and anxiety is important.

At the same time, while validating a patient’s experience, I try to reassure distraught individuals with mild paralysis that we’ll work to make things better, and also that the majority of casual observers won’t notice the weakness. People with facial paralysis can also suffer from body dysmorphic disorder and have other psychosocial situations that can make their experiences and treatment more difficult.

MM: Unfortunately, patients with facial paralysis frequently see providers who tell them “There’s nothing to do,” or “It isn’t that bad; others have it worse.” These statements can add to the distress patients with facial paralysis experience as they not only create a feeling of hopelessness, but they can also make patients feel bad about seeking treatment. Facial paralysis has a strong association with depression, anxiety, and social withdrawal, and these statements make these mental health issues worse.

No matter how long a patient has had facial paralysis and what caused their paralysis, there are always treatment options. I just performed selective denervation surgery on someone who had facial paralysis for almost 50 years, and they had a great result! Patients need to be informed that there are options to manage their facial paralysis ranging from targeted facial physical therapy, to chemodenervation, to surgical procedures.

ENTT: What are the advantages to having patients treated at facial nerve centers versus by an individual surgeon? What other team members make a difference in treatment/recovery?

BA: “The management of facial palsy is complex and does require a team of individuals with different specialties, which includes a facial plastic surgeon, neurologist, neurosurgeon, neuromuscular rehab expert, and a head and neck oncologist. Teamwork and the ability to communicate effectively is essential to getting the job done when multiple team members are required.”

LH: I think that multidisciplinary care breeds discovery. Seeing these patients in silos without any other input blunts the ability to see improvement in multiple dimensions. I am better when I have the input of my facial physical therapist and I know my patients have better outcomes when therapy is introduced early. I have patients who, for financial or travel distance reasons, cannot commit to seeing our FNMR therapist. These patients don’t have the same understanding of their disease process, their recovery process, and less consistent outcomes.

ML: At a facial nerve center the team is a collaborative group of individuals that understand the unique challenges of facial paralysis and the important contribution of all specialists involved in their care. At our center, we have multiple surgeons who can come together to plan the best surgical intervention. We also have physical therapists, a speech therapist, and optometrists that help with dry eye care.

MM: Patients with facial paralysis frequently require targeted facial physical therapy (aka neuromuscular retraining), chemodenervation, surgery, and mental healthcare. As such, a multidisciplinary facial nerve center team should include a facial reanimation surgeon, a therapist, and a psychologist or psychiatrist who has experience in caring for patients with mental health issues associated with craniofacial conditions. Other important team members include head and neck cancer surgeons, neurotologists, and ophthalmologists.

Having all these team members as part of a facial nerve center allows efficient scheduling and delivery of care for patients. Team meetings permit critical collaboration where experts come together to develop the best treatment plan for patients.

ENTT: How would a physician start a facial nerve center if one doesn’t exist at their facility?

BA: The most critical component to starting a facial nerve center is putting together a leadership and team who are passionate for treating patients with facial palsy! Everything else is really based on teamwork and dedication to providing the best possible care and treatment for your patients.

ML: Many people, including those in the medical field, aren’t aware of the cutting-edge treatments available for facial paralysis. Educating your local community can be a good way to network and find others interested in the care of patients with facial paralysis.

Without your own otolaryngology–head and neck surgery department, neuro-otologists and head and neck surgeons are great allies and also treat patients with facial paralysis. Ophthalmology is another department often involved in the care of patients with facial paralysis. Oculoplastic surgeons often treat ectropion and optometrists create special scleral lenses for dry eyes. Neurology also treats patients with paralysis and will often do chemodenervation treatments. Plastic surgeons, particularly those with craniofacial training and arm/peripheral nerve expertise, can also have a shared interest.

At our institution, partnering with the rehabilitation groups in physical therapy and speech therapy has both improved the care we offer and has helped us grow our referral base. Don’t hesitate to reach out to existing facial nerve centers to ask about they were developed. It can be really helpful to talk to others.

MM: Starting a facial nerve center begins with recognizing the complexity of care patients with facial paralysis frequently require. Like most of medicine, it helps if a physician has a passion for caring for patients with facial paralysis. Ideally, they’ve received sub-specialized training in facial reanimation and, if not, this should be a prerequisite for starting a facial nerve center. There are many AAFPRS fellowships available that can provide this type of training. Facial nerve therapists typically have a background in physical therapy or speech language pathology, and there’s an online course therapists can take through Facial Therapy Specialists International to obtain specialized training.

Once a team is in place, they should introduce themselves to local practices including otolaryngology, neurology, ophthalmology, dermatology, and internal medicine groups; these practices frequently interact with facial paralysis patients.

Lastly, once a physician starts treating patients with facial paralysis they must perform rigorous data collection, including photos, videos, and patient-reported outcomes. Collecting and studying these data is how we can continue to advance as a subspecialty and improve the care we offer patients with facial paralysis.