INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic endonasal surgery (EES) for skull base lesions has advanced considerably. The transplanum transtuberculum approach is commonly used for anterior skull base lesions, where maximizing the anterior sphenoidotomy in the superior part is crucial for ensuring direct visualization and creating a wide working corridor. This procedure involves manipulation near the olfactory neuroepithelium; however, with a reported olfactory dysfunction risk. Although reports have detailed EES use for suprasellar lesions, methods for avoiding olfactory impairment remain unclear. A recent report revealed that EES for tuberculum sellae and planum sphenoidale meningiomas caused new post-operative anosmia in 21% of cases, warranting further investigations of the methods used to avoid olfactory impairment. The present report describes an EES technique that we devised for suprasellar lesions, which maximizes upper anterior sphenoidotomy while preserving the olfactory mucosa. We also evaluated the surgical outcomes, including a quantitative assessment of olfactory function.

Explore This Issue

September 2025METHODS

Study Design and Setting

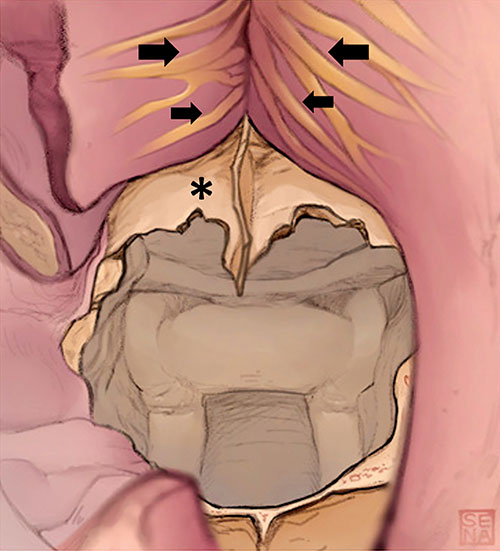

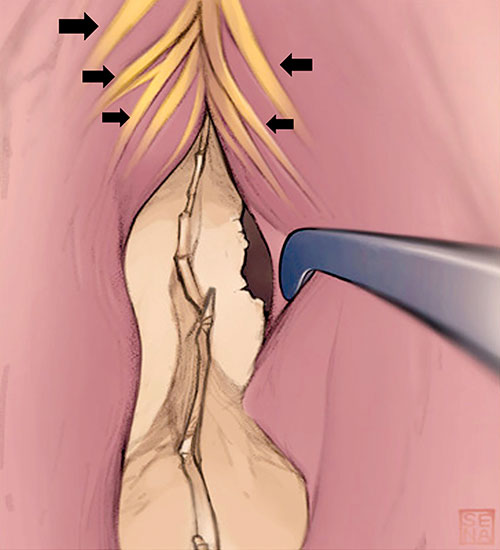

Figure 1. Schematic drawings showing the first step of superior maximization of anterior sphenoidotomy. After the nasal septal mucosa was carefully separated in a subperiosteal layer, the bony nasal septum was resected. The anterior wall of the sphenoid sinus and the vomer bone were exposed, and the ostium of the sphenoid sinus was identified. Olfactory filaments (arrows) are visible through the periosteum.

Figure 2. Schematic drawings showing the second step of superior maximization of anterior sphenoidotomy. The olfactory mucosa on the nasal septum was gently elevated, with olfactory filaments (arrows) visible through the periosteum. This procedure exposes the bony structure at the upper end of the anterior wall of the sphenoid sinus (asterisk), without damaging the olfactory mucosa.

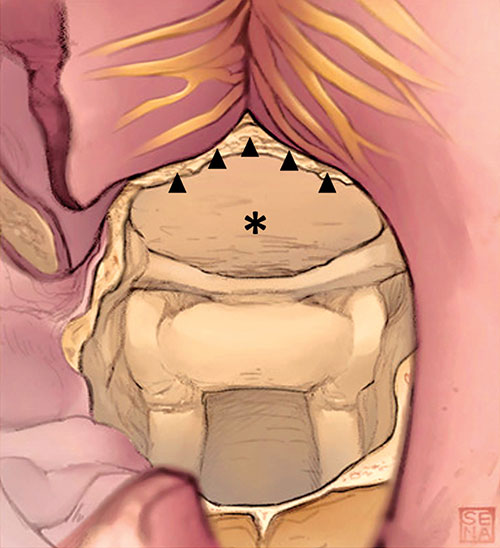

Figure 3. Schematic drawings showing the final step of superior maximization of anterior sphenoidotomy. The upper part of the anterior wall of the sphenoid sinus was completely removed up to the level of the skull base (arrowheads), with the olfactory mucosa fully preserved. After this procedure (maximizing the superior aspect of anterior sphenoidotomy), the planum sphenoidale (asterisk) was widely exposed and well visualized under a straight endoscope.

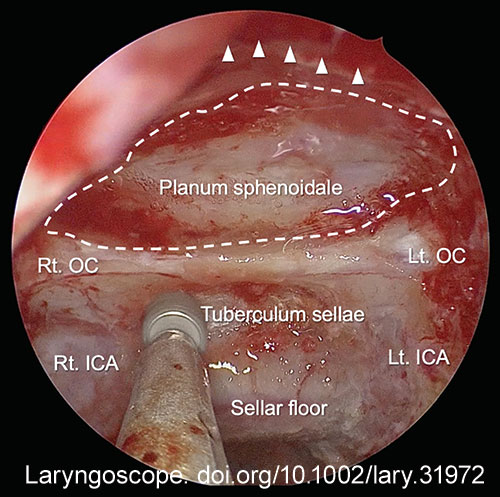

Figure 4. Endoscopic view after superior maximization of anterior sphenoidotomy in a representative case of tuberculum sellae meningioma. The anterior wall of the sphenoid sinus was removed to the level of the skull base (arrowheads). Panoramic view of the planum sphenoidale (dotted line) was obtained. Anatomical landmarks inside the sphenoid sinus are widely seen. Rt. OC = right optic canal; Lt. OC = left optic canal; Rt. ICA = right internal carotid artery; Lt. ICA = left internal carotid artery.

Leave a Reply