INTRODUCTION

The accessory parotid gland (APG) is a salivary tissue anatomically separated from the main parotid gland, located between the skin and the masseter muscle, with a reported prevalence of 32%. Tumors arising from APG account for 1 ~ 7.7% of all parotid tumors, existing with a higher frequency of benign lesions. Among APG tumors, pleomorphic adenoma (PA) is the most common benign type, followed by mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) as the most common malignancy. Although relatively rare, an APG tumor should be considered when a non-tender mass is detected in the mid-cheek region.

Explore This Issue

April 2025Surgical resection is the recommended first choice of treatment for APG tumors. Accessing the APG region through conventional Blair or facelift incisions can be challenging, requiring extensive flap elevation and longer operation duration. The cheek incision is also recommended and thought easy to perform, but it leaves a visible external scar. Compared with the direct transcutaneous incision, the transoral approach has been increasingly carried out in recent years, with better post-operative cosmetic effects. Furthermore, advancements in endoscopic instruments and techniques have provided a promising alternative for the resection of APG tumors, mitigating the injury to anterior facial nerve branches and Stensen’s duct (SD) due to enhanced visualization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

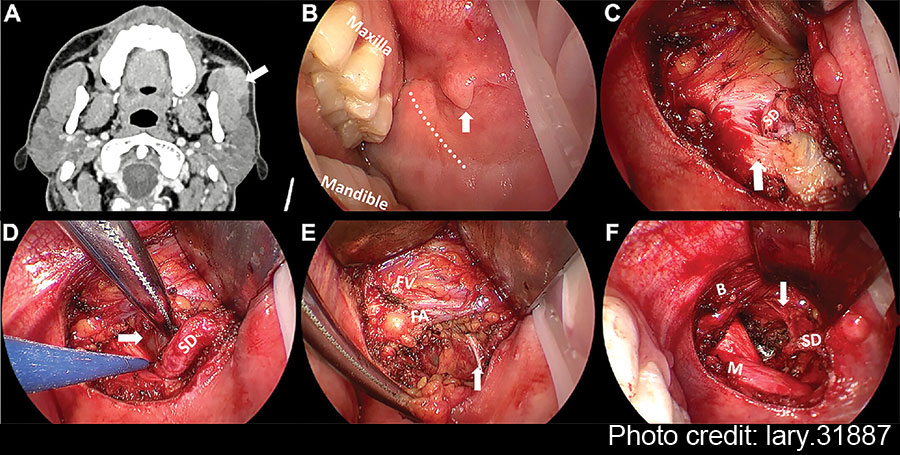

The selected case was a 30-year-old male with a chief complaint of a painless, slowly growing mass in the left cheek for three months. Pre-operative ultrasonography and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) identified a well-circumscribed mass measuring 2.5 × 1.9 cm within the APG region, adjacent to the surface of the masseter muscle (Fig. 1A). Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) did not provide a definitive diagnosis. With the desire to avoid an external obvious scar, the patient opted for the endoscope-assisted transoral approach we proposed. The patient was thoroughly informed about the advantages and disadvantages of this procedure, as well as the potential for conversion to a standard conventional approach if necessary. Given the involvement of the intra-oral incision, it was advisable to conduct thorough dental prophylaxis pre-operatively to reduce the risk of infection. Post-operative cosmetic outcomes and patient satisfaction were evaluated six months after surgery using a visual analog scale (VAS), ranging from 0 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (no visible scar and very satisfied). The operation was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Surgical Technique

Under general anesthesia and nasotracheal intubation, the patient was placed in a supine position with the shoulders raised by a surgical drape. The opening of the SD was clearly identified (Fig. 1B) under the magnification and illumination of an endoscope (5 mm, 0-degree rigid scope, STORZ, Germany). Based on the anticipated location of the APG tumor on the pre-operative contrast-enhanced CT, an approximately 4-cm transoral incision was made anterior to the left pterygomandibular ligament over the mass. When incising the buccal mucosa, submucosa, and buccinator muscle layer by layer, a monopolar electrocautery could be used to manage bleeding. The mucosal flap and buccinator muscle were elevated together to ensure an adequate operative field. With further blunt dissection, the facial artery and facial vein were gradually exposed and preserved. Care should be taken to ascertain the location of the SD when separating the anterior border of the masseter muscle (Fig. 1C). The APG mass was revealed following the retraction of the buccinator muscle and the anterior masseter muscle, aligning with the SD (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1: Pre-operative CT and intra-operative images under endoscopic view. (A) The axial contrast-enhanced CT of left APG mass. (B) Pay attention to SD papilla when designing the incision (vertical arrow). (C) The relationship between SD and anterior masseter muscle (vertical arrow). (D) The identification of APG tumor (horizontal arrow). (E) The exposure and protection of buccal branch of the facial nerves (vertical arrow). (F) The surgical bed after the removal of APG tumor. The branch of the facial nerves was identified clearly under magnified view (vertical arrow). APG = accessory parotid gland; B = buccinator muscle; FA = facial artery; FV = facial vein; M = masseter muscle; SD = Stensen’s duct.

Thyroid retractors were then replaced by deep surgical retractors to obtain a wider view of the oral cavity for easier manipulation. Blunt dissection was performed along the tumor capsule and SD posteriorly to separate the surrounding tissue. The APG, buccal fat pad, and part of the parotid were excised together with the mass. At this step, the endoscopic view allowed for clear visualization of the branches of the facial nerves, facilitating the separation and protection (Fig. 1E). In addition, a long bipolar electrocoagulation was recommended for tissue separation due to its precise coagulation capabilities, minimizing damage to adjacent critical tissue and reducing bleeding.

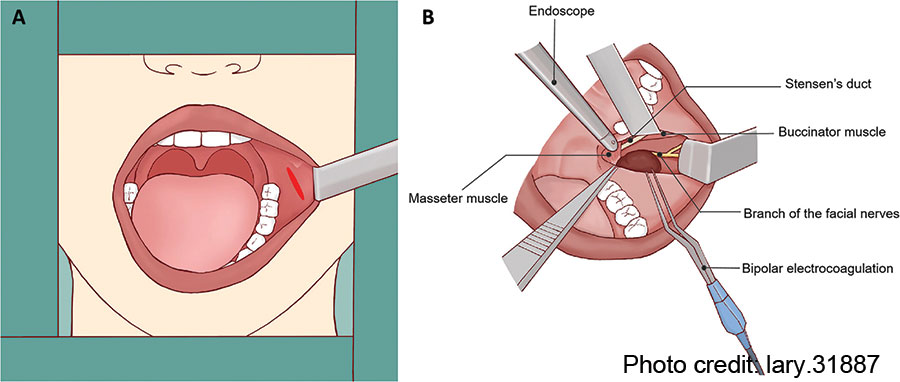

Following the removal of the APG tumor and part of the surrounding tissue without any macroscopic rupture, the surgical field was irrigated with saline solution. The SD and buccal branch of the facial nerves were preserved completely (Fig. 1F). The intra-operative frozen pathology confirmed the diagnosis of pleomorphic adenoma; thus, the conventional parotidectomy was not conducted. Finally, the oral wound was closed with 4–0 absorbable sutures with a rubber drainage strip inserted, which would be removed two days after surgery. The macroscopic operative field and related anatomical structures surrounding the APG tumor were presented in the illustration (Fig. 2). To prevent a salivary fistula, a bandage was applied to the parotid area for approximately one week.

Figure 2: Illustration of the operative field and related anatomical structures. (A) Using surgical retractor to obtain adequate exposure for transoral resection of APG tumor. (B) Anatomical landmarks surrounding the APG tumor.

RESULTS

The procedure was completed within 85 minutes, without conversion from the endoscope-assisted transoral approach to the conventional parotidectomy via Blair incision. Post-operatively, there were no visible facial external scars left, leading to brilliant aesthetic outcomes. The patient used a soft assisted feeding tube to consume a liquid diet six hours after the surgery. The final immunohistochemical report revealed pleomorphic adenoma, consistent with both the pre-operative diagnosis and frozen pathological report.

The patient remained hospitalized for two days post-operatively and was discharged as scheduled. There were no reported complications such as facial paralysis, wound infection, or bleeding issues observed at a follow-up period of six months. The patient reported high satisfaction with post-operative cosmetic outcomes and facial nerve activity.

CONCLUSION

Our reported experience outlines the procedure and tips for endoscope-assisted transoral APG tumor resection. Future prospective multicenter studies with large sample sizes and longer follow-up duration are necessary to further assess the safety and clinical feasibility of this modality. In summary, for suitable benign cases, the endoscope-assisted transoral excision of APG tumors deserves to be further considered in clinical practice.

Leave a Reply