Explore This Issue

May 2014

A new survey of otologists in North America, sporting an impressive 50% response rate, has shown that the use of intra-operative facial nerve monitoring (FNM) is no longer limited to tumor surgeries that have a high risk of iatrogenic facial nerve damage. Rather, nearly 90% of the respondents said they are now using FNM even during mastoid surgery, according to Jack M. Kartush, MD, a pioneer in facial nerve monitoring who conducted the survey and agreed to share the results exclusively with ENTtoday.

“This really was a surprising finding,” said Dr. Kartush, emeritus professor at the Michigan Ear Institute at Wayne State University in Detroit. “I expected most otologists to say they virtually always used facial monitoring for tumor cases, especially since monitoring was strongly advised in the 1991 NIH Consensus Conference Statement. But to see that nearly 90% of North American otologists monitor all of their mastoid operations was remarkable. It indicates that facial nerve monitoring is approaching being considered a standard of care—even in lower risk cases.”

Dr. Kartush underscored the real-world utility of the survey results. “The otologists were asked what their actual clinical practice was—not just their opinion of what they believed was a standard,” he said. He added that 94% of the respondents were fellowship trained and thus had one to two years of additional post-residency training and a high surgical volume. If such a highly specialized group uses FNM routinely, “then it follows that less experienced surgeons should have at least the same need to monitor the facial nerve,” he pointed out.

Dr. Kartush offered three caveats regarding FNM:

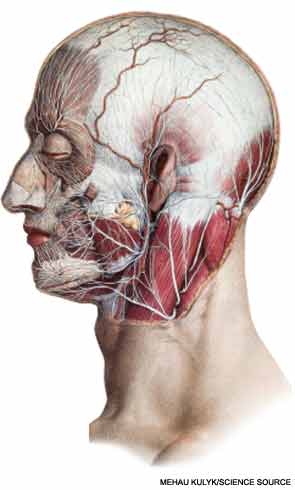

- Monitoring is not a substitute for knowledge of anatomy or surgical skills;

- Poor monitoring is worse than no monitoring; and

- Monitors fail less frequently than do “monitorists.”

In other words, no technology provides a fail-safe system for preventing human error, he said. That explains why most of the lawsuits he is asked to review now rarely make a “failure to monitor” claim, he noted. Instead, the cases typically cite “failure to monitor correctly.” That’s why proper training in FNM “is essential and drives a need for otolaryngologists to have clinical practice guidelines that not only suggest which cases should be monitored, but [also] how monitoring should be properly performed.”

Unfortunately, determining which procedures are appropriate candidates for FNM continues to be a hotly debated topic. Hoping to spur support and uptake of FNM, Dr. Kartush wrote the American Academy of Otolaryngology’s (AAO) first position statement on facial nerve monitoring two decades ago. Several years later, he followed up that effort by submitting a proposal for FNM practice guidelines to the AAO.

What the Guidelines Should Contain

Dr. Kartush reiterated that FNM guidelines need to present information not only on which cases should be monitored but also on how monitoring should be done. But those two areas of focus are not enough, he pointed out: The guidelines also must stipulate who is qualified to monitor. Here is how such a content framework could be fleshed out, he said:

- How to correctly monitor the facial nerve. Topic areas should include placing recording electrodes properly, performing a “tap test” on the electrodes, checking the electrode impedance, and using electrical stimulation routinely to assure that current is flowing and that facial muscles have not been inadvertently paralyzed by anesthesia’s use of neuromuscular blockade drugs. “These can be done like a pilot’s pre-flight checklist,” Dr. Kartush said.

- Who should perform monitoring. “If we solve the first item, we resolve the second,” he noted. “That is, if we can prove via guidelines and cited data that otolaryngologists have training and background to properly perform both the technical and interpretive aspects of FNM, that should convince insurers, neurologists, and neurophysiologists that we are well suited as a specialty to do this.”

- Which cases should be monitored. “This has been the most controversial area in the debate over FNM,” Dr. Kartush said. “But the survey is demonstrating unequivocally that FNM has now been adopted in the actual clinical practices of the great majority of otologists for tumors, tympanomastoid surgery, cochlear implants, endolymphatic sac decompressions, and transmastoid labyrinthectomy. Conversely, the survey also demonstrates that, while FNM might have a role in very low-risk procedures, most otologists do not at this time monitor every stapes or pure tympanoplasty operation.”

Reimbursement

Until such guidelines are drafted and released, another long-simmering controversy over FNM—over who should be reimbursed for the procedure—will continue. Dr. Kartush noted that Medicare, Medicaid, and many third-party insurers now refuse to pay otolaryngologists for facial nerve monitoring. In fact, their payment policies often stipulate that while other clinicians aside from the surgeon can get paid for the monitoring, the surgeon who elects to do it will not be paid.

Leave a Reply